Zimbabwe’s waste pickers waiting impatiently for COVID-19 vaccines

For the waster pickers of Bulawayo, COVID-19 has posed risks to both their health and their incomes. Hope for a vaccine is reaching fever pitch.

- 19 August 2021

- 4 min read

- by Tendai Marima

Khumbulani Tshuma, 44, is getting agitated. It’s nearly midday and he’s been waiting for four hours to get his first jab of COVID-19 vaccine at Richmond Landfill Site on the outskirts of Bulawayo, Zimbabwe’s second industrial city. The disjointed queue isn’t moving, but he can’t leave.

He needs the jab.

Tshuma is one of scores of waste pickers whose daily bread comes from scrambling through the trash looking for recyclable materials. He tilts his cowboy hat to avoid the glare of the winter sun.

“I’ve lost a whole day’s work just waiting and waiting,” he says.

“I use two pairs of gloves when I work and I have a mask so I’m not really scared of getting COVID-19, but I need this vaccine to protect me even more,” he explains.

For six years, Tshuma has picked through the city’s rubbish collecting cardboard boxes and plastic bottles for recycling.

Despite the risk of contracting the deadly COVID-19 virus from the trash heaps, some unmasked collectors are compelled to pick through dirty piles of garbage for survival.

The waste tip, locally known as Ngozi Mine, was established in 1994 as one of three landfill sites in Zimbabwe and, at present, the Bulawayo City Council collects at least 7,200 tonnes of waste per month. All of it is discarded at the landfill. As a result of COVID-19, waste pickers face a number of risks, including handling potentially contaminated materials.

The impact of the pandemic on the waste pickers goes beyond health risks. Trawling through Ngozi Mine has provided thirty-seven-year old Isaac Sibanda with the means to educate and support his family. Yet, since the start of the first lockdown in March 2020, and the continued lockdown in 2021, his daily takings have been low.

Have you read?

“Right now we aren’t getting as much money as during normal times so it’s tough,” he says. “The supermarkets and factories don’t open like they used to so there isn’t as much to pick. I hope if COVID-19 ends with this vaccine then business will go back to normal for me.”

While the pandemic’s end seems a remote prospect right now, the country’s mass vaccination drive aims to achieve herd immunity, which would see shops open for more than seven hours and the reopening of bars and public gatherings. For Sibanda, longer trading hours would mean more waste and potentially more money for him.

City health director Edwin Sibanda has warned against free movement despite the ongoing vaccine roll-out: “The whole city is basically a hotspot as people move around freely and we need to curb that if we want infection cases to reduce. We have engaged private health practitioners to assist with inoculation.”

Public health institutions are mandated to vaccinate, but the Ministry of Health has authorised private health providers to immunise people for a nominal maximum fee of $5 (ZWL $434.35).

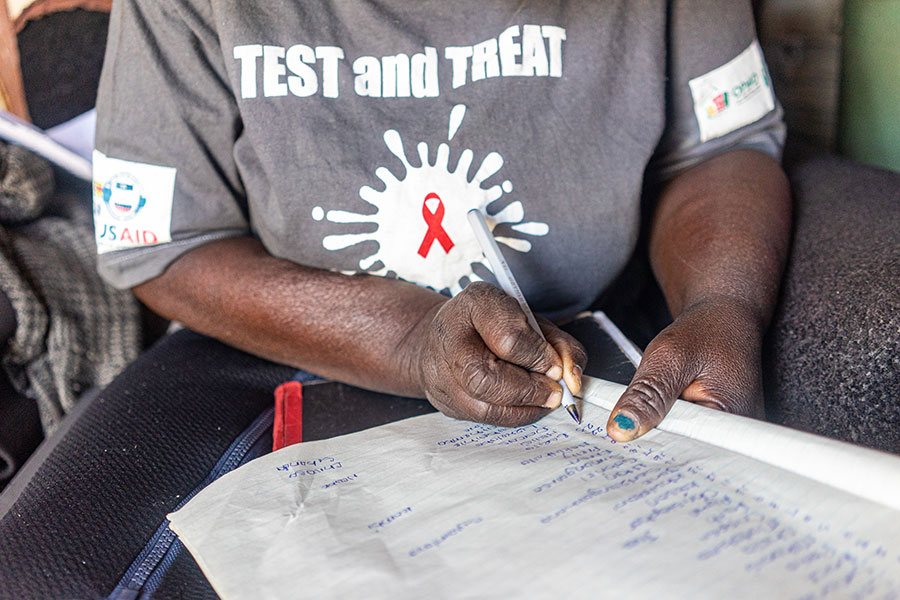

Ngozi Mine’s community health worker, Sithembile Ndlovu, 51, who lives at the informal settlement, says the change in attitude makes her hopeful. When she did her first house rounds informing people of the vaccines, she faced stiff resistance.

“People were afraid in the beginning. Just like with ARVs (antiretroviral drugs used to treat HIV), they didn’t want to take the vaccine, but we’ve really tried to educate people,” she explains.

Sadly, it took the death of an elderly resident earlier this year to change minds in Ngozi Mine.

“We don’t really know what happened, but when we looked at him, we could see had serious breathing problems and he was very ill. When the hospital said the cause of death was COVID-19, it was a real shock,” Ndlovu says.

Having lived at Ngozi Mine since its inception in 1994, Ndlovu is keenly aware that, despite inoculation, there is a persistent risk marginal communities face without access to potable water.

“We have no water and we have no sewage system here. COVID-19 is prevented by water and living in a clean environment, but, without water, how do we prevent COVID-19?” she asks.

The pandemic has also adversely affected access to health care. Ndlovu oversees the health needs of more than 200 homes with over 500 children and the continuous cycle of lockdowns has impeded her work.

“I’m not able to do the outreach work I used to do. If someone is sick, I can’t assist them. I don’t have some basic pills and bandages in my first aid kit. Right now, if someone gets hurt, I can’t help them,” she sighs.

All pictures credit: Gavi/Tendai Marima/2021

Twitter and Instagram @i_amte

More from Tendai Marima

Recommended for you