What we learned from tracking every COVID policy in the world

For one year, 600 people tracked 20 types of coronavirus restriction in 186 countries – here's what they found out.

- 26 March 2021

- 6 min read

- by The Conversation

In March 2020, as COVID-19 swept around the globe, my colleagues and I began debating the bewildering new measures popping up around the world with our master’s students in a politics of policymaking class at the Blavatnik School of Government at Oxford University.

We had a lot of questions. Why were governments doing different things? Which policies would work? We didn’t know. And to answer those questions, we needed comparable information on these new policies, including school closings, stay at home orders, contact tracing and more.

A few weeks later, we launched the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker to help find these answers. It has now become the largest repository of global evidence relating to pandemic policies.

To date, more than 600 data collectors from around the world have helped us track 20 different categories of coronavirus response, including lockdown, health, economic, and now vaccine policies in 186 countries.

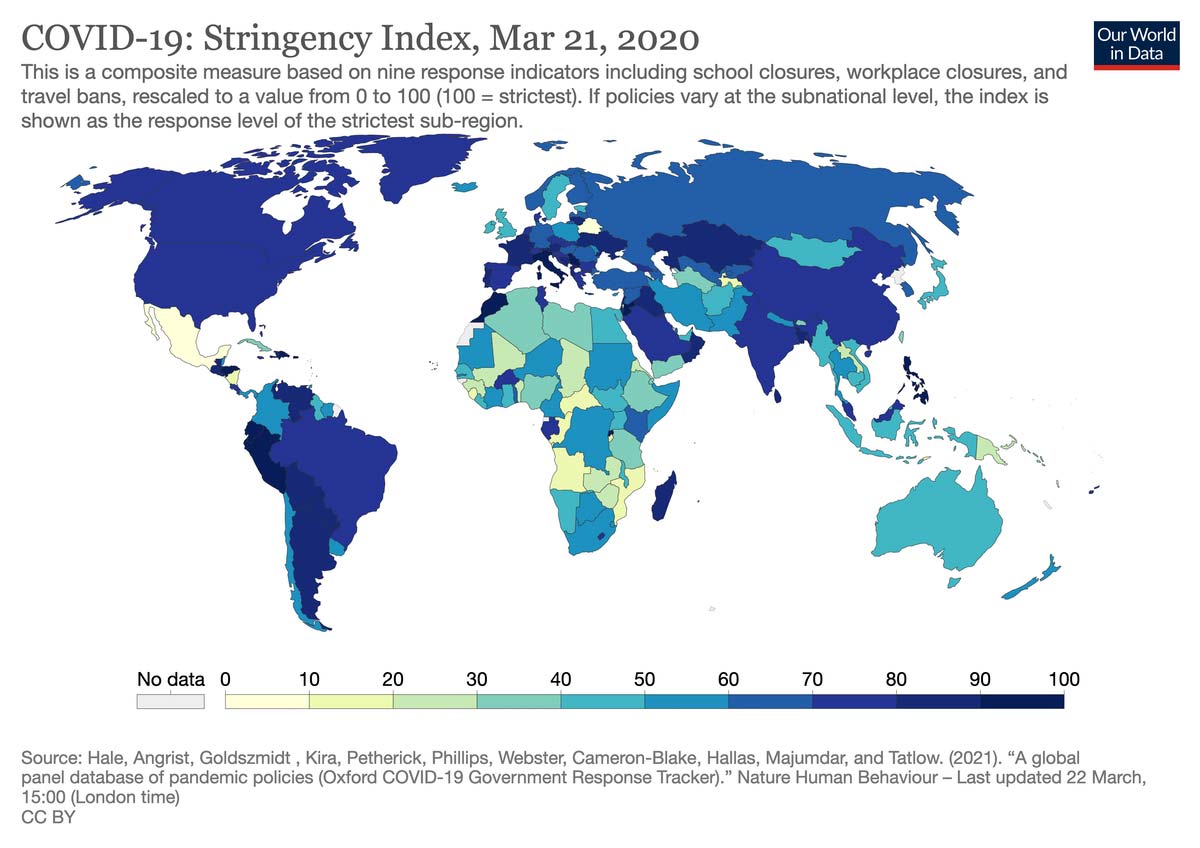

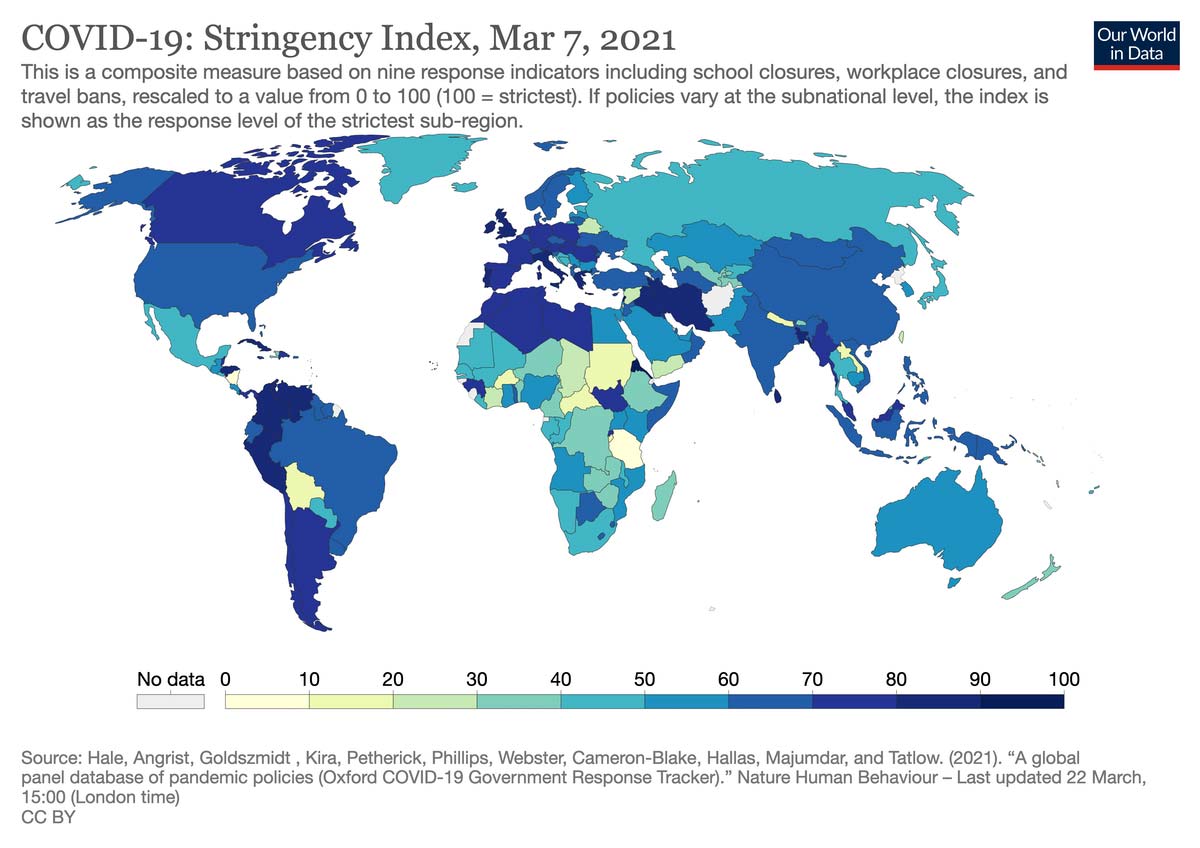

We then group those policies into a number of indices, including the stringency index, which records the number and intensity of closure and containment policies on a scale of zero to 100. Fifteen countries reached 100 on the stringency index, while seven never surpassed 50. The countries with the highest average stringency were Honduras, Argentina, Libya, Eritrea and Venezuela. Those with the lowest were Nicaragua, Burundi, Belarus, Kiribati and Tanzania.

A year on, what else have we learned about how governments have handled the largest health crisis in memory?

One surprising observation is that similarities can actually outweigh differences. During the first months of the pandemic, governments mostly adopted similar policies, in mostly the same sequence, at mostly the same time – the two middle weeks of March 2020.

Have you read?

But as the pandemic progressed, countries – and, in some parts of the world, states and regions – began to vary considerably.

Some governments were able to contain the first wave and then preserve those gains with a mix of targeted closure and containment measures, extensive testing and contact tracing, and firm international border controls.

Places like China, Taiwan, Vietnam and New Zealand all managed not just to flatten the curve but to keep it flat, albeit with a few small flare-ups. In our data, we count 39 countries that have only experienced one wave of disease, though limited testing and reporting systems, or government suppression of information, make it hard to determine the true number.

Other countries have had less success, seeing second, third, or even fourth waves of disease. Some of these have been relatively small outbreaks, controllable with test and trace measures and targeted restrictions. For example, South Korea and Finland, though not able to eliminate the virus, have largely kept it from stressing health systems.

Rollercoaster countries

Too many countries have been on a veritable rollercoaster of rising and falling infections with corresponding policy whiplash and tragic death tolls. The United States, United Kingdom, South Africa, Iran, Brazil and France have seen successive waves of disease and have phased in and out of restrictive policies.

Though initially debated, the scientific literature is now clear: COVID-19 restrictions work to break the chain of infection, with timely, sharper restrictions having greater effect than slower, weaker ones.

But while clearly true on average, there is no guarantee this recipe will always work. Countries like Peru suffered rising disease despite restrictive policies, perhaps showing that compliance and trust are also key to effectiveness. Some evidence also suggests that stronger economic support makes COVID-19 restrictions more effective.

Money isn’t everything

While we can identify patterns of successful response, it is also evident that none of the country characteristics that were expected to provide an advantage before the pandemic, such as wealth or autocracy, have clearly done so.

If you divide the world into countries with above average and below average deaths, robust government responses and weak ones, you will find in both groups plenty of rich countries and poor countries, democracies and dictatorships, those ruled by populists and those governed by technocrats.

Success and failure are moving targets. As the pandemic has evolved, so have government responses. According to our data, vaccines are now available in 128 countries and rising. Notably, some of the countries most swiftly rolling out vaccination – Israel, the UK, the United States, the UAE – are places that have previously struggled to control the virus through restrictions and test-and-trace systems.

Lessons for the future

One year on, the pandemic is by no means over, but already our data suggests some implications and lessons for governments.

First, old ideas about what contributes to pandemic preparedness need to be updated. Some countries with formidable scientific and healthcare capacity stumbled mightily. At the same time, places with less capacity, including Mongolia, Thailand and Senegal have managed to largely keep people healthy and the economy running.

Second, learning from others, or even from past experience, cannot be taken for granted. In March 2020 eastern European countries like the Czech Republic, Hungary, and Bulgaria saw what happened to their western neighbours and imposed restrictions before community transmission became widespread. They largely avoided the death tolls many western European countries experienced in the first wave.

But then just a few months later some of the same eastern European countries did the exact opposite, waiting too long to reimpose measures as cases rose in the autumn, with all too predictable consequences.

Finally, while our work has tracked individual governments’ responses, it is clear that exiting the pandemic will require global cooperation. Until transmission is curtailed throughout the world with restrictions and vaccinations, the risk of new variants sending us back to square one cannot be ignored.

In the first year of the pandemic we saw little cooperation between governments. In the next, we will need to work together to control this disease.

Authors

Thomas Hale

Associate Professor in Public Policy, University of Oxford

Noam Angrist, Emily Cameron-Blake, Lucy Dixon, Laura Hallas, Saptarshi Majumdar, Anna Petherick, Toby Phillips, Helen Tatlow, Andrew Wood, and Yuxi Zhang contributed to this article. It is published in collaboration with the International Public Policy Observatory, of which The Conversation is a partner organisation.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Disclosure statement

Thomas Hale receives funding from UKRI's Economic and Social Research Council through a project titled the International Public Policy Observatory, of which The Conversation is also a partner.

Partners

University of Oxford provides funding as a member of The Conversation UK.

More from The Conversation

Recommended for you