What is behind the sudden international spread of monkeypox?

The virus may be exploiting a change in population behaviour and increased global travel but it can still be stopped from spreading further, say scientists.

- 25 May 2022

- 5 min read

- by Priya Joi

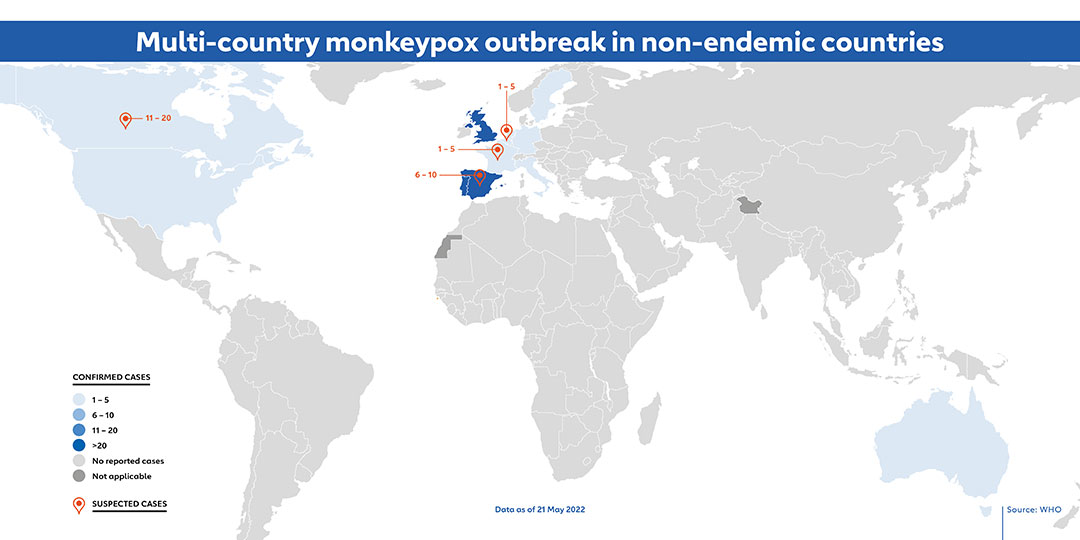

What started as one unusual case of monkeypox has now spread to several countries, with many cases having no link to Central or Western Africa where the disease is endemic. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) most recent estimates from 21 May (see map) indicate that there are around 100 cases in 12 non-endemic countries, though there could be around 300 confirmed or suspected cases in 16 non-endemic countries.

“The virus appears to have gotten lucky and has hit parts of the population where people have been in close contact with each other and also travel internationally.”

Isolated cases of the disease have been seen in the past in the US, Singapore and UK but there have usually been just one or two cases before the disease has burned out on its own.

Scientists are puzzling over how a disease that is not easily transmitted has been able to spread to so many countries and between so many people.

The right place, at the right time

“The virus appears to have gotten lucky,” says Dr Lee Hampton, medical epidemiologist at Gavi, “and has hit parts of the population where people have been in close contact with each other and also travel internationally.”

“The current outbreak in non-endemic countries suggests that sustained human-to-human transmission is quite feasible, so it suggests that ongoing human transmission could also be happening in Africa on a larger scale than generally thought.”

Another factor is that routine immunisations against smallpox stopped in the early 1970s in places like the US and UK. As smallpox vaccines can be 85% effective at preventing its related virus, monkeypox, many people born after that time are not immune anymore.

The good news, Hampton says, is that “it is less transmissible than COVID-19 and it’s not an airborne virus or one that can be aerosolised as COVID-19 can be, and in hospitalised patients, just using standard precautions (mask, gown and gloves) is completely effective in preventing transmission.”

He points out that this doesn’t mean it will die out on its own, though, as the spread of the virus indicates we will need rapid and aggressive containment measures, including targeted vaccination with the smallpox vaccine, to contain the clusters.

Human-to-human transmission

Scientists are racing to find out more about monkeypox. Much of our knowledge about the disease comes from the 1970s and 1980s, and the world has changed greatly over the last few decades. This means that the epidemiology – our understanding of who gets sick and why – of the disease is likely to have changed too. Also, the virus has been studied in specific settings in West and Central Africa, and viruses don’t necessarily behave the same in different contexts.

Hampton explains that: “This current international outbreak is clearly behaving differently from previous ones.” Monkeypox had previously spread via chains of transmission that were usually two or three people long, at most seven people long, so many cases were due to zoonotic transmission from infected wild animals. Human-to-human transmission was not continuous.

Have you read?

Since the spread of the virus is not linked to imported cases, WHO has warned the cases identified so far could be “the tip of the iceberg” in both endemic and non-endemic countries.

Dr Hampton also notes “The current outbreak in non-endemic countries suggests that sustained human-to-human transmission is quite feasible, so it suggests that ongoing human transmission could also be happening in Africa on a larger scale than generally thought.”

So far, WHO says mass vaccination is not yet needed, and targeted vaccination strategies with vaccines from the smallpox stockpile, as well as other public health measures such as quarantine and isolation, can contain the outbreaks.

Searching the genome for mutations

A team of scientists in Portugal have released the first draft genome of the monkeypox virus from the current outbreak, and it looks most similar to the strains found in 2018 and 2019 in UK, Israel and Singapore.

So far it is not clear whether or not the virus has mutated, which could explain its sudden ability to spread more widely than previously in non-endemic countries. As a DNA virus, monkeypox is less likely to undergo significant mutations than a RNA virus like SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, but such mutations are possible.

But this may take time to determine as the monkeypox genome is much larger than that of SARS-CoV-2 – it has around 200,000 DNA letters compared with 30,000 RNA letters, and is not as well studied.

Mass vaccination not yet needed

Given that many of us lucky enough to have access to COVID-19 vaccines may now be on our third or even fourth doses, there have been questions over whether we would need mass vaccinations to stop the spread.

So far, WHO says mass vaccination is not yet needed, and targeted vaccination strategies with vaccines from the smallpox stockpile, as well as other public health measures such as quarantine and isolation, can contain the outbreaks.

Moderna is testing potential vaccines in pre-clinical trials. Although the smallpox vaccines do work well against monkeypox, most contain replicating live virus and carry some risks.

So far none of the cases in non-endemic countries have had severe disease or have died – unlike in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, where more than 1,200 people have become infected with monkeypox and 58 have died since January this year.

As the infection is clearly visible – through a rash and fever – and spreads only through close contact, quarantining sick people can achieve a lot in stopping the spread, says Dr David Heymann, an infectious disease specialist at WHO.

He adds: “There are vaccines available, but the most important message is you can protect yourself.”

More from Priya Joi

Recommended for you