South Sudan’s polio vaccination campaigns are bearing fruit

South Sudan has systematically implemented campaigns to eradicate polio in the country. Hard-working vaccinators are striving to keep it that way.

- 8 September 2021

- 4 min read

- by Winnie Cirino

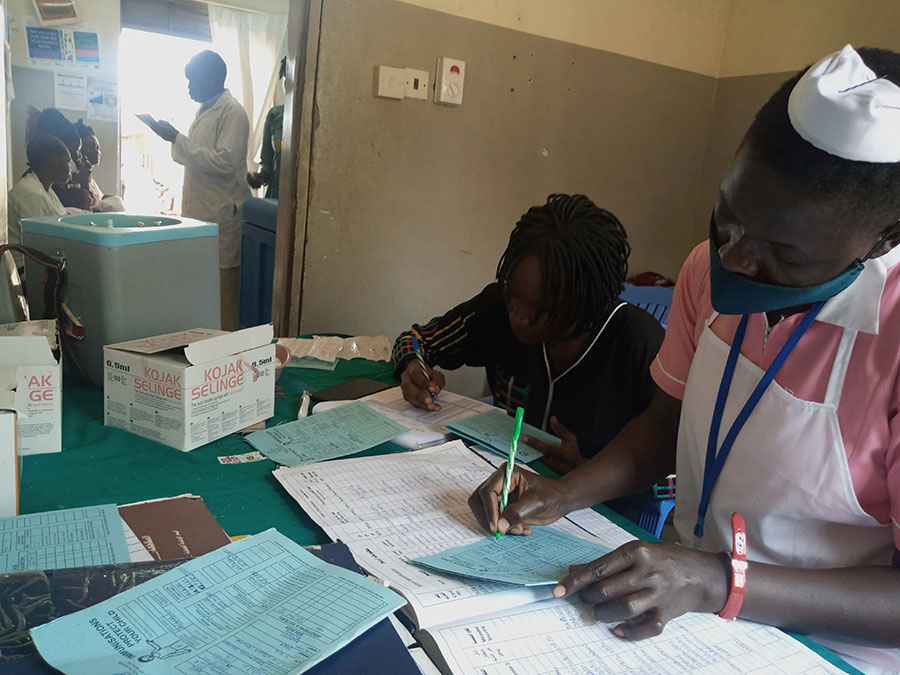

Jane Paya, a vaccinator at Munuki Primary Health Centre in Juba, has been vaccinating children for 12 years. Every morning when she reaches the office, she finds mothers waiting for her with their babies. Before she vaccinates the children, she briefs the mothers on the various immunisations.

“I talk to the mothers and ask them what vaccines they have brought their children to be vaccinated with,” Paya says. “For those that say they don’t know, I teach them. For example, I tell them that BCG is given to prevent tuberculosis.”

The World Health Organization declared South Sudan polio free in 2019. The last case of wild polio virus was reported in 2009.

“I ask them, the one that they put two drops in the mouth, which disease does it prevent? Some will say they were taught its polio while others say they don’t know. I will also take time to explain about polio and the vaccine,” she adds.

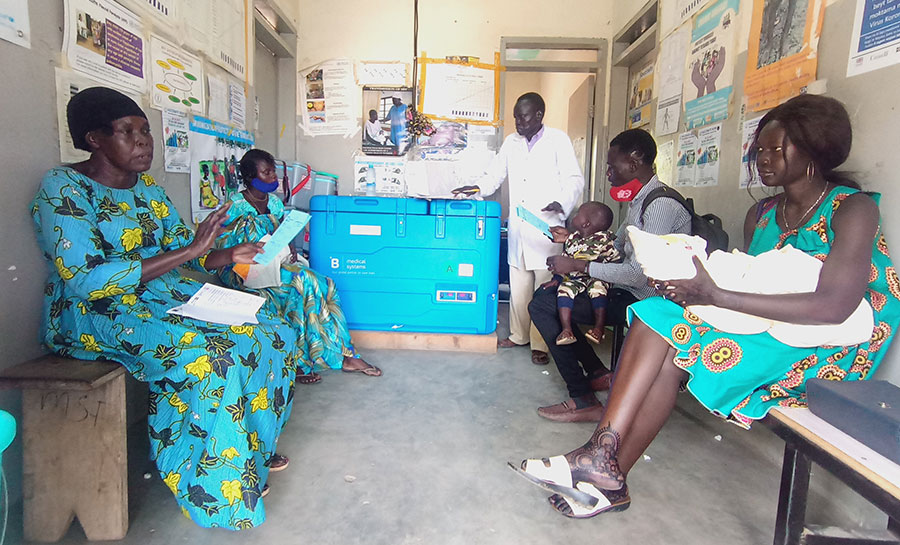

She also uses picture charts to show the mothers what a child looks like when infected with a specific disease. After the lessons, she and her colleagues then collect the vaccination cards from the mothers and start vaccinating the children. They generally vaccinate over 100 kids a day.

Mother of four, Jane Yangi brought her youngest child for BCG and Pentavalent vaccines at the Munuki Health Centre. Yangi has always made it a priority for all her children to be vaccinated against serious diseases, especially polio.

“I’m scared of the physical disability, especially polio, and therefore it is important that my baby receives all the vaccines and that I follow the process to the end, she says.

Have you read?

The South Sudan Health Ministry launched a polio vaccine campaign earlier this year to reach children from all parts of South Sudan as few parents take their children to the health centres for vaccination. The target was to vaccinate over 2.8 million children with Oral Polio Vaccine (OPV).

So far approximately two million children have been vaccinated, according to George Awzenio, the Director of the Expanded Programme on Immunisation at the Health Ministry. He says the slow speed is caused by mother’s reluctance to take children to health centres for vaccination.

“We’re now moving from house to house, so that will help. As a result, we should be able to cover more than 95 percent of our target. With routine immunisation, we only end up covering about 60 percent of the children, which is why we are doing this campaign to reach all children within South Sudan,” Awzenio explains.

Health care worker Lillian Nene has been going door to door to vaccinate children in and around Korijik village, Juba. Nene says the polio vaccine campaign has helped mothers feel free to vaccinate their children.

“I talk to the mothers until they are comfortable with my giving the vaccine. I vaccinate in the villages where there are few people. At times, we cross the river to Geriza Island where there are many children. When I am done with one village, I move to the next one the following day. I vaccinate between 50 and 60 children daily,” she proudly explains.

The World Health Organization declared South Sudan polio free in 2019. The last case of wild polio virus was reported in 2009.

For Awzenio, this means that their campaign is doing well and health workers have managed to sensitise mothers to the importance of the polio vaccine.

“Now all the mothers know that the vaccine is very good for their children and are automatically bringing their children to the health facility. This is even the case when there are no health facilities in their area and they have to travel kilometres to a facility in the city. For example, the people in Jebel Ladu don’t have health facilities, but we see mothers making the seven-kilometre trip to bring their children to Juba,” he says.

Sacha Bootsma, a doctor with the World Health Organisation in South Sudan says there is a system now installed in the country to search for any child that is diagnosed with acute flaccid paralysis that could be polio. She says polio campaigns are regularly run in South Sudan because people are always on the move.

“We might have missed a lot of children in a campaign because, in an environment like South Sudan where people are mobile and constantly migrate, it can be difficult to capture all the children we need to vaccinate,” she says.

In Dr Bootsma’s view, the system ensures that the country can get rid of polio disease in the long term.

“We want to get rid of polio and the only way to do that is to make sure all children have had the three doses of the polio vaccine,” Dr Bootsma concludes.

More from Winnie Cirino

Recommended for you