Slipping through the cracks: Urban under-immunisation on Bengaluru’s margins

In 2020, 16 million children in lower-income countries did not receive the third dose of their basic childhood vaccines. 12.4 million of them didn’t even receive their first dose. Despite a perception that missed children typically belong to hard-to-reach, remote communities, a great number of the live hidden in plain sight.

- 19 November 2021

- 7 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

Like tens of millions of Indians, 26-year-old daily wage worker Basavaraj and his wife Mohanamma are raising their children on the margins of a mega-city, far from their village of origin. Their home in the southern metropolis of Bengaluru is part of a cluster of 300 improvised blue plastic yurts – tarpaulin sheeting lashed to scrap-wood frames – hugging a section of railway that runs through a suburb called Hebbal. This was once the northern extent of the city, gazing out over fields, but Bengaluru long ago burst its bounds, and Hebbal is now shaded by concrete apartment towers and snaking flyovers.

As the mushrooming city pulls in migrant labour from the countryside, ramshackle settlements like this one spring up to accommodate some of the poorest among them. It’s a hard place to raise a young family in safety. Few public services reach the community: there is no electricity and no running water. On the stormiest days of the monsoon, puddles merge into ponds on indoor floors. Residents use the railway tracks as a latrine, a risky practice compelled by the absence of proper sanitation. Just weeks ago, a ten-year-old deaf-mute boy was struck by a train and killed as he relieved himself.

Other threats, likewise born of privation, advance more slowly. Among them is an elevated risk of preventable infection: in ‘invisible’ communities like this one, vaccination rates can dip well below the wider city’s average. Hardship compounds hardship: a study recently published in The Lancet Global Health found that India’s unvaccinated or “zero-dose” children “continue to be concentrated among socially disadvantaged groups,” including poor families and families with less-educated mothers. Missed children were more prevalent in “urban areas including large populations of migrant or informal sector workers” – in other words, in places like this.

Credit: Vivek Muthuramalingam

Basavaraj and Mohanamma’s younger son, nine-month old Prashanth, numbers among the at-risk, having so far received only two of the nine vaccines the Government of India recommends for a child his age. “I haven’t seen the medical centre here yet, this is new to us,” Basavaraj explains, holding his elder boy, three-year-old Hanumantha, on his lap. He’d rather take Prashanth to a government hospital back in their village – 500 kilometres away – than seek out healthcare in the city.

Credit: Vivek Muthuramalingam

It’s a common story in communities like this one, says Simon Fernandes of Diya Ghar, an NGO that has been providing foundational education and nutrition to the children of Bengaluru blue-tent settlements, including this one, since 2016. “They are an unrecognised community,” he explains. “They are people who have fallen through the cracks of what the government is providing for the underprivileged.” That, along with pervasive social discrimination, erodes trust in urban facilities, according to Fernandes.

Often, Fernandes says, the people living in the blue tents assume they’ll be home soon. Often they’re wrong. “They think: we are going to be here for six months, eight months, because I had a medical emergency, and I took a loan, and now I have to repay that loan,” he explains. “But the reality is that next year, or six months from now, something else comes up. I’ve seen people living here for 10, 15, 20 years in much the same conditions.” Temporary disconnection from public health services gradually becomes chronic.

Social discrimination is a factor acting against equitable vaccine coverage in cities across the world, says researcher Rachel Belt, a consultant on zero-dose children with the Gavi Health Systems and Immunisation Strengthening team. It might be targeted, direct: if health workers insult or dismiss a person belonging to a marginalised group, that patient is less likely to return. Other times, the system simply fails to reckon with the practical realities of a highly mobile and poor population. There are cities, Belt says, in which census lines have been drawn to exclude informal settlements, allowing vulnerable residents to disappear from the data of public oversight. “In some countries, people have come from another region or country and they are not registered. They could be asked to show a card, and they don’t have it,” she adds. Vaccination may be free, but the costs of transport can still be prohibitive. Even when health centres are within easy reach, they may only open during working hours.

The nearest clinic to the Hebbal settlement offers vaccination on specific days of the week, using a token-based queuing system, Jeeva, a Diya Ghar teacher explains. On those days, the clinic is thronged; the wait can cost parents a full day’s pay. Several of the women at the Hebbal settlement who work in trash segregation and recycling earn just Rs 300 (USD 4) a day. For them, a day without work may mean a day without food.

Credit: Vivek Muthuramalingam

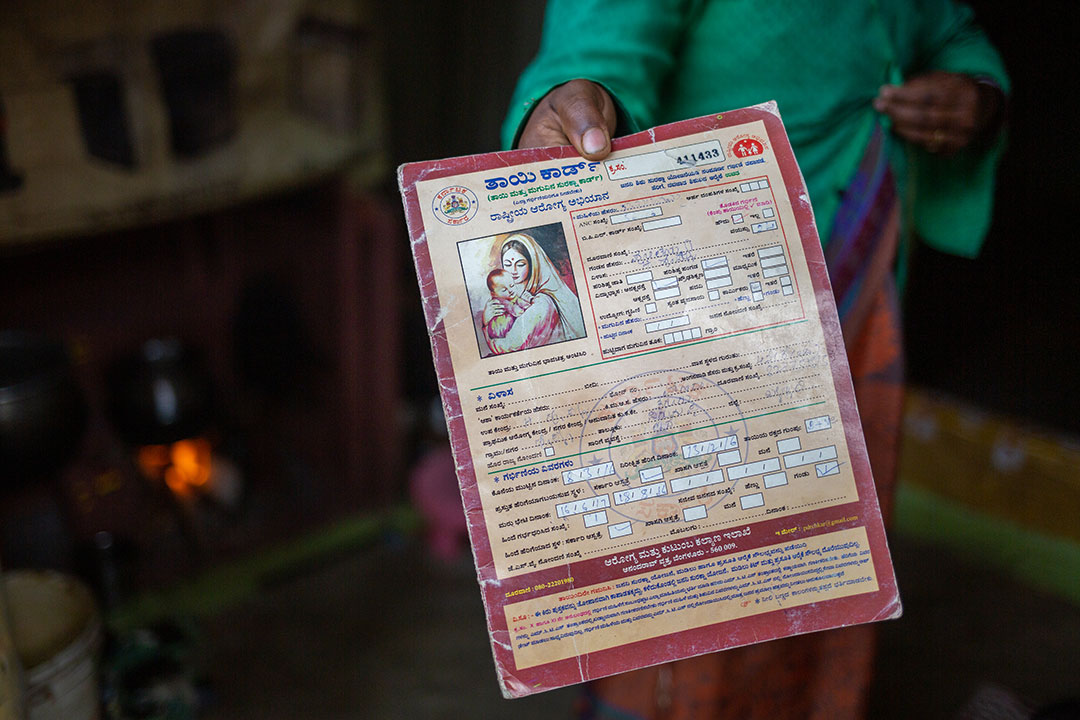

At our request, Diya Ghar conducted an informal survey of the parents of young children in eight of the eleven blue-tent settlements the NGO serves, in an effort to quantify just how ‘missed’ these missed-out communities are. Only 50 to 60% of the migrant families interviewed self-reported meeting the regular vaccination schedule. Many of those who said they had fallen behind explained that their “Mother Card,” which logs a child’s vaccinations, was at home in the village.

One such parent is Subbamma, aged 25. Originally from the neighbouring state of Andhra Pradesh, Subbamma lives in a blue tent community at Horamavu, whose residents earn a living by guiding sacred bulls through community streets, requesting alms. Though both of Subamma’s children, a five-year-old son and a three-year-old daughter, were born at a Bengaluru hospital, and both received a shot of vaccine at birth, she says she only brought her daughter for follow-up jabs when she was six and ten weeks of age. Based on the typical immunisation schedule, it’s reasonable to imagine that her children remain completely unprotected from deadly measles, and are still vulnerable to a number of other dangerous infections.

But Subamma has had more than enough to worry about during the last couple of years. Hunger has been a pressing threat. During the lockdowns of 2020 and 2021, she and her family survived on charity – donated dry rations, nutrition kits put together for children by Diya Ghar. For her, as for millions of other migrants in India, pandemic policy, more than the SARS-CoV-2 virus, landed as an instant, existential threat. The cracks of public health protection widened: in 2020, the country reported a 6% dip in routine vaccination coverage.

But a longer-lens view tells a more optimistic story. While 33.4% of Indian children were unvaccinated in 1992, that number stood at 10.1% in 2016. Across low-income countries, the number of zero-dose children fell by 14% between 2015 and 2019. Though the pandemic pushed the number of zero-dose children up in 2020, health systems are learning how to reach the hard-to-reach – and hopefully, beginning to see the hard-to-see.

Meantime, Basavaraj and Mohanamma are planning a trip north, 500km along the rails, to Yadgir. There, says Basavaraj, they’ll take their baby to the doctor. “We know,” Mohanamma says, “that vaccination is needed to prevent major illness in the future.”

Research on missed children points to the vital importance of forming partnerships with community organisations who work with disenfranchised communities. VaccinesWork would like to thank Diya Ghar for their help in telling this story.

Full photo gallery

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you