Sick words: The etymology of disease

What are we really saying when we utter a diagnosis?

- 7 April 2022

- 7 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

When it comes to disease (early 14th century, from old French – literally a lack of ease) science often moves faster than language, and the words we assign to the things which make us sick are often stranger – and more revealing – than we realise.

Even when the intention is not political, naming illnesses for places can have troubling indirect effects.

Bad etiology

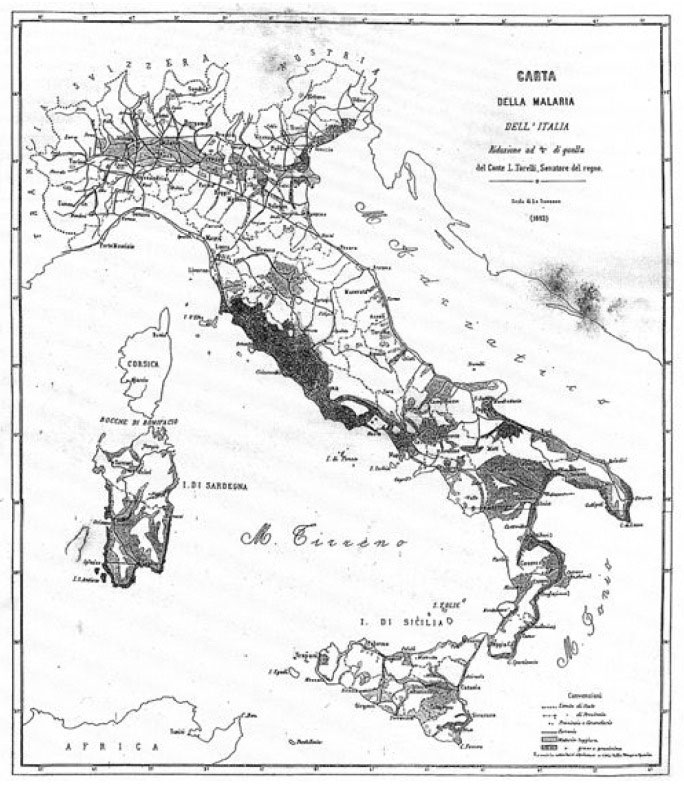

Malaria’s name is a souvenir of a long-since-corrected medical misunderstanding.

The parasitic infection, which is transmitted by the female Anopheles mosquito, kills more than 600,000 people a year, the vast majority of them in Africa. But before the mid-20th Century, malaria was common also in Italy, particularly in the swampy places along the Tiber where the moist, noxious air hummed with insects. Eighteenth century physicians spotted the link to the marshland, but drew the wrong conclusion, blaming the fatal fevers on the mala aria, or mal’aria – the bad air – instead of the winged, blood-sucking vectors and their pathogenic payload.

Credit: ResearchGate – Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic

Also stemming from the Italian, and landing even wider of the etiological mark, is influenza. Originally a generalised name for any disease outbreak deemed to be caused by the influence (influenza in Italian, as in the Latin influentem – “flowing in”) of the stars, it was applied as “influenza di catarro” to a spate of illnesses in 1743 (catarro, or catarrh in English, is a build-up of mucous or a disease characterised by it).

Spreading across Europe, that phlegmy epidemic carried its moniker into English as simply “influenza”, where it came to refer more specifically to the acute respiratory viral infections we most usually complain of as “the flu” – not realising that when we do, we’re indirectly cursing the stars for our sniffles.

Plural pox

It’s strange for a disease with such an outsize history of destruction to be packaged in such a diminutive name: when smallpox landed in the New World aboard a Spanish ship in 1520, it sparked an epidemic tidal wave that would kill, with help from measles, influenza and bubonic plague, a staggering 90 percent of the continent’s pre-Colombian indigenous population.

This was an impact so great it caused the planet to cool. By then, it was already familiar in Europe and elsewhere, often as an endemic sickness that carried off 20-60% of those it struck, covering their bodies with blistery pox, also spelled pockes, a Germanic-origin word meaning ‘pustule’.

But why so small? This poxy affliction needed distinguishing from the likewise dreaded Great Pox, an illness which began with an ulcer at the (usually intimate) site of infection. In its secondary stage, the Great Pox caused fevers, rashes, sore throats. In its terrible end-phase, it damaged the heart, produced deforming bumps in bone and skin and other organs, and ate at the skull and brain, causing dementia and insanity before it killed its victim.

If the “Great Pox” rings no bells, that’s probably because in 1530, a Venetian physician and poet called Girolamo Fracastoro wrote a narrative poem in which he invented a mythical ‘patient zero’ of the disease, a young shepherd called Syphilus, whose name has since attached itself to the bacterial STI known to us as syphilis.

Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

And then there are the chickenpox – according to Samuel Johnson’s 1755 dictionary, a sickness called chicken “from its being of no very great danger”. Despite not having any actual epidemiological relationship to farmyard fowl, the viral infection was, as far as pockmarking illnesses went, duck soup.

Symptom or mood?

In Italian and French and Greek, the words for rabies – rabbia, rage, and lyssa– mean both a disease and an emotion: the fatal viral infection and the feeling of wrath. We draw our version of the term from the Latin rabere – to rave, to be mad.

Were the outward manifestations of fury and the sickness which can turn patients uncharacteristically aggressive similar enough to confuse? Probably not – though it’s clear that once, before germ theory explained sickness in microbial terms, the lines between sentiment and symptom were less distinct: a feeling, after all, is a feeling whether it’s a sting or a joy.

But even so, it could still only have been the form of rabies we redundantly call “furious rabies” that could have passed for supercharged anger, since the other sort is paralytic.

Have you read?

Use the adjective “rabid” to describe an explosively angry person, or even an excessively dedicated fan, and you traipse across the feelings-illness boundary in the other direction – committing, each time, a metaphoric conflation that Susan Sontag would have warned you against.

But, as rabies proves, if you travel back in time, her famous injunction becomes unworkable. Hippocrates might have explained to you that illness and mood were both a function of imbalanced humours: blood, yellow bile, black bile and phlegm.

There are vestiges of humoral theory dotted through our dictionary. Cholera, the acute and deadly diarrhoeal disease that we understand now to be caused by the bacterium Vibrio cholerae, gets its name from the Greek word cholē, meaning bile. A choleric, however, is neither a patient, nor a patient person, but a hot-tempered, irascible one – a semantic collision which only makes sense if you believe that an excess of bile makes for a constitutionally cranky character.

Victim blaming

Not long after the conclusion of their 1976 annual convention in Philadelphia, attending members of the American Legion became acutely ill with chest pains, vomiting, confusion and diarrhoea. Twenty-nine out of the 182 “legionnaires” who fell ill later died. The cause turned out to be a previously undiscovered bacterium – and the affliction became known as Legionnaire’s disease, linking the infectious threat forever to its first victims.

That naming an illness for its sufferers risks stigmatising vulnerable groups ought, perhaps, to have been obvious to the health establishment. But in the early 1980s, when a new immune disorder began sickening and killing “primarily male homosexuals” in the United States, researchers dubbed the sickness “GRID,” or gay-related immune deficiency. The press soon branded it the 4H disease, because it was considered by then to primarily affect Haitians, homosexuals, haemophiliacs and heroin users.

The epidemic swelled, broke the banks of its earliest epithets and became a global pandemic under the more accurate acronym of AIDS, for “acquired immunodeficiency syndrome” – a syndrome acquirable, it shouldn’t need to be noted, by anyone with human biology and insufficient access to treatment.

Political football

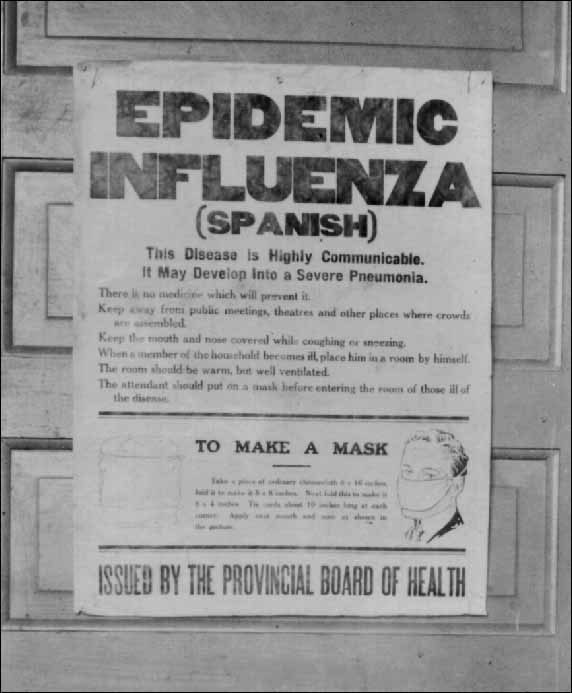

By the time so-called Spanish Flu of 1918 began, nobody imagined the stars were to blame. But if people thought it came from Spain, they were wrong about that too – its common name was a function of politics, not a record of its origins.

Spain was rare in Europe for remaining neutral during World War I, allowing its media to report the news more freely than in its warring neighbour countries. By the time the sickness – the deadliest influenza on record – made headlines in Madrid in May 1918, it had been spreading across the world for at least three months.

Credit: Provisional Board of Health, Alberta, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Though that first known outbreak took hold at a military base in Kansas, the Spanish, not knowing that, termed the dreadful sickness the “French Flu”. It wasn’t the first time that a disease name had become an international hot potato. At points in its history syphilis, that especially stigmatised affliction, has been called “the French disease” (by Germans, Italians and Brits), “the Neapolitan disease” (by the French), the “Polish disease” (by the Russians), “the German disease” (by the Polish), and the “Spanish disease” (by the Danes, Portuguese and northern Africans). The Turks went broad and labelled it a “Christian disease”; the Muslims and Hindus of northern India tagged each other.

Even when the intention is not political, naming illnesses for places can have troubling indirect effects. Should we have known better by 2011 than to call Middle East Respiratory Syndrome what we did? Probably.

But maybe we are finally learning our lesson. In 2015, WHO issued guidance on best practice in assigning labels to diseases. It might be working: despite the best efforts of certain highly audible political figures, COVID-19 is not known as “the Chinese virus”, and, since the WHO’s alphabetical intervention, new variants are no longer identified by the countries which first discovered them. “Omicron” may not be a catchy designation, but at least it doesn’t implicate its victims.

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you