A million a day: Pakistan’s COVID-19 vaccine campaign hits its stride

After a halting start to its immunisation campaign, Pakistan has shifted into high gear, now administering a million doses a day. #VaccinesWork spoke to national health leaders and spent a morning at a rural vaccination centre to find out what the country’s battle against COVID-19 looks like on the ground.

- 21 October 2021

- 6 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

If you were judging only on the mood at the rural health centre at Tarlai, a COVID-19 vaccination site on the edge of Islamabad, you might think that Pakistan’s immunisation campaign is taking it easy.

“Increasingly, as we go along, the role of COVAX is becoming more prominent and important.”

On a recent morning, the street bordering the Tarlai clinic was noisier with the complaints of crows than the buzz of traffic or conversation, and vaccine recipients strolled up unhurriedly, in twos and threes, shaded from the sun by a row of eucalyptus trees.

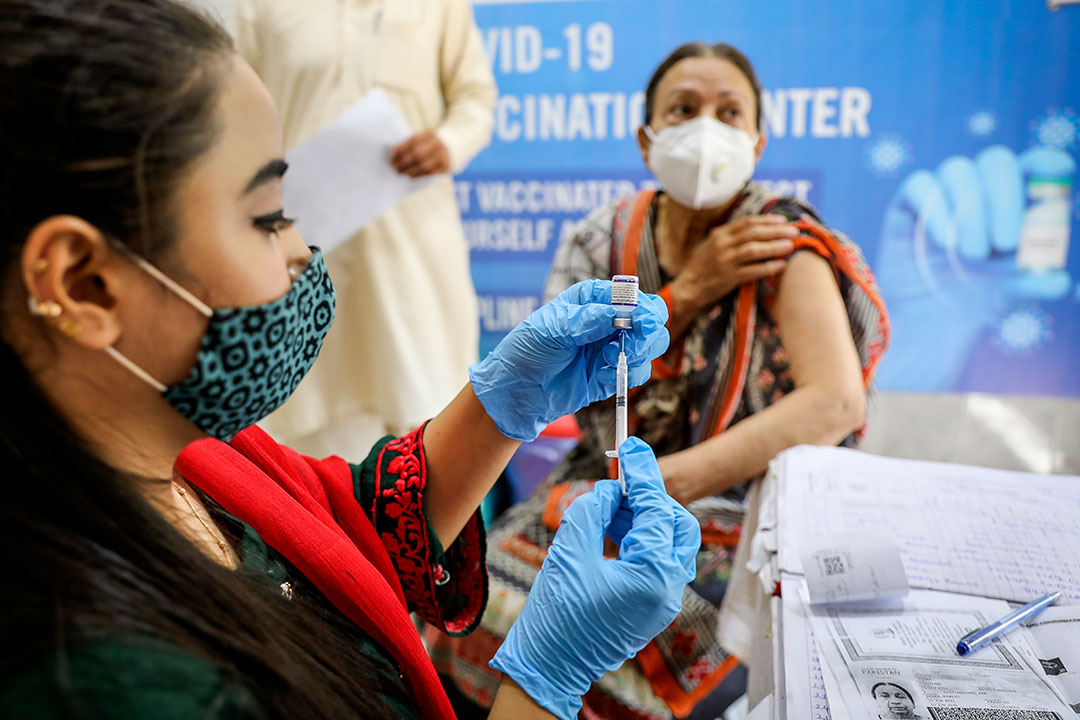

Indoors, the procedure of the COVID-19 vaccine roll-out ticked over with practised calm. Ceiling fans hummed as two men tapped patient details into the National Immunization Management System, confirming which vaccine was due, which dose. Blue-gloved vaccinators measured liquid quantities from vials into syringes under steady, appraising gazes and delivered them into bared upper arms as patients flinched, just a little. Notes were made in registers, vaccinees guided into observation rooms. The next person was called in, then the next. “A great system is working here,” said Dr Sadia Naaz, the health centre in-charge.

Bustle, it turns out, is a poor metric for forward motion. Eight months into the campaign, RHC Tarlai is averaging 1,000 vaccinations a day. Pakistan’s daily tally is touching an impressive one million.

Gavi/2021/Asad Zaidi

It’s a striking change of pace from just a few months ago, when the country was inoculating fewer than 400,000 people a day. “We really need to ramp up our vaccinations,” Faisal Sultan, infectious disease expert and Special Assistant to the Prime Minister on Health, told Voice of America in late May.

Today, Sultan speaks of the roll-out with more satisfaction: a million doses constitutes “a large daily deployment” – a success. But more than just doing big numbers, he emphasises, Pakistan is doing big numbers well. Early on, the vaccination figures showed a worrying gender skew – women, it seemed, weren’t showing up to clinics in the same numbers as men. Over time, and with the deployment of greater number of mobile vaccination units and a greater number of female vaccinators, that gap has narrowed. Now, he says, “I think this is an example of a very fair, non-discriminant, equitable roll-out of a public good. This is how it ought to have been, and we are very happy that this is how it has actually happened.”

Sultan’s assessment is shared by Alexa Reynolds, Gavi’s Pakistan team lead. “The Gavi Secretariat and the COVAX facility acknowledge Pakistan’s remarkable achievements in COVID vaccination,” she wrote in an email. “Pakistan continues to find effective and innovative ways to ensure the broadest possible access to COVID vaccines.” More than 28% of the population have now received one dose, Reynolds noted.

Have you read?

It’s taken more than a few tweaks to get to this point. “The system had to retool itself a bit,” Sultan told VaccinesWork. Pakistan’s existing immunisation infrastructure was built for routine childhood immunisation, meaning it was geared towards the very youngest members of society. A fair COVID-19 vaccine rollout demanded distribution, first, to the oldest. “But I think it [Pakistan’s Expanded Programme for Immunisation] had the inherent strength,” Sultan says, “to be able to smoothly roll out COVID-19 vaccines as well.”

Dr Muhammad Akram Shah, the EPI’s National Programme Manager, agrees. EPI had built-in advantages: highly developed access to communities, “the best communication teams”, and a well-oiled supply chain – a branched network linking federal warehouses to provincial, divisional and district stores. These made swift adaptation to the COVID-19 rollout possible, but the pivot didn’t come cheap. As the system redirected to confront the coronavirus, routine immunisation coverage took a hit. “We have to acknowledge that, yes, it was a big pressure on Pakistan, but now, Alhamdulillah, we are recovering again in the routine immunisation,” he says.

Vaccine storage facilities have also required modification. The existing cold chain worked for some COVID-19 vaccines, but was unsuitable for others, like the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines, which demanded storage at minus temperatures – in “ultra-cold chain” (UCC) conditions. With months of support and hard work from partners, including Gavi, WHO and UNICEF, under country leadership, Pakistan scrambled and constructed a limited UCC network concentrated at the centre and in big cities.

Good luck lent a hand: stability studies showed that the Pfizer vaccine could be thawed down to 2-8 degrees centigrade for 31 days. “That’s made our lives very easy,” Akram Shah says. “We have cold chain equipment for 2-8 degrees everywhere in Pakistan.” He adds, “Probably there will be no problem in rolling out Pfizer across Pakistan.”

The huge infrastructure built to tackle polio in the country has also been crucial, with the country’s COVID-19 vaccination programme built jointly on the existing Expanded Network for Immunisation (EPI) and polio programmes. The entire data system which is monitoring the rollout, for example, was initially created to help Pakistan in its efforts to finally eliminate polio.

The Pfizer jab is the most recent addition to Pakistan’s COVID-19 vaccine arsenal, with a first consignment of 3 million COVAX-delivered doses landing in the country in late August. “A country like Pakistan, with, you know, over 220 million people, has to depend on multiple sources,” says Dr Faisal Sultan. “Increasingly, as we go along, this role from Gavi COVAX is becoming more prominent and important.”

Gavi/2021/Asad Zaidi

At RHC Tarlai, two ice-lined refrigerators house Pfizer doses, which the government is making available, free of cost, to children aged 12 and up – an important step to ensure Pakistan’s safety as schools across the country reopen.

Widened eligibility isn’t the only reason the demographic profile of vaccinees arriving at the centre has shifted. Dr Amreen, who has worked at Tarlai for the past four or five months, has particularly noticed an uptick in the number of women presenting themselves for vaccination, and credits that turn to growing awareness: more people in Pakistan becoming more informed about vaccines.

Some of that shift is probably down to positive top-down messaging, like the banner in the clinic reassuring pregnant women about the safety of the jab. Some has filtered organically through the community, like from Masroor Ali, freshly inoculated with his second dose of Sinopharm, to his older neighbours and family members, whom he says he “convinced”. Either way, Dr Amreen says, “now, we are on a good track.”

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you