Louis Pasteur, monster slayer

Rabies haunted humanity for millennia before the Parisian father of microbiology embarked on a quest for a vaccine. It amounted to a wager: if Pasteur succeeded, then even this most diabolical of afflictions would be proven microbial, rather than monstrous, in nature.

- 23 March 2022

- 8 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

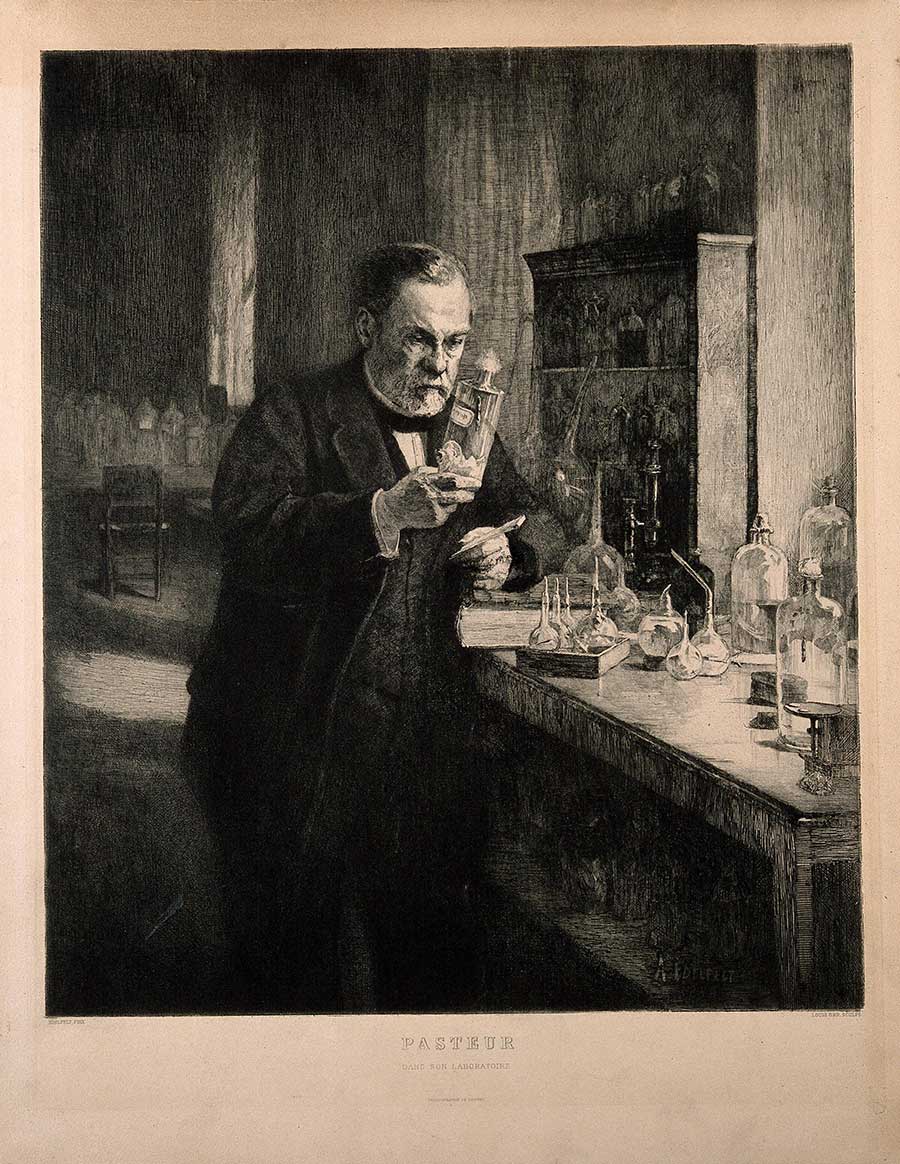

1881: Louis Pasteur has resolved to figure out rabies, so now his Rue d’Ulm lab howls with the agonies of several caged and deranged canine inmates. There are Poodles and Bulldogs and Great Danes, and more to come: Paris’s vets know the scientist is in the market for mad dogs.

Rabbia in Italian means rabies and anger; rage in French and lyssa in Greek straddle the same semantic line. Rabies wrote the script for familiar monsters, like vampires and werewolves, who prowl the shadow spaces of acceptable society and transmit their iniquities by bite.

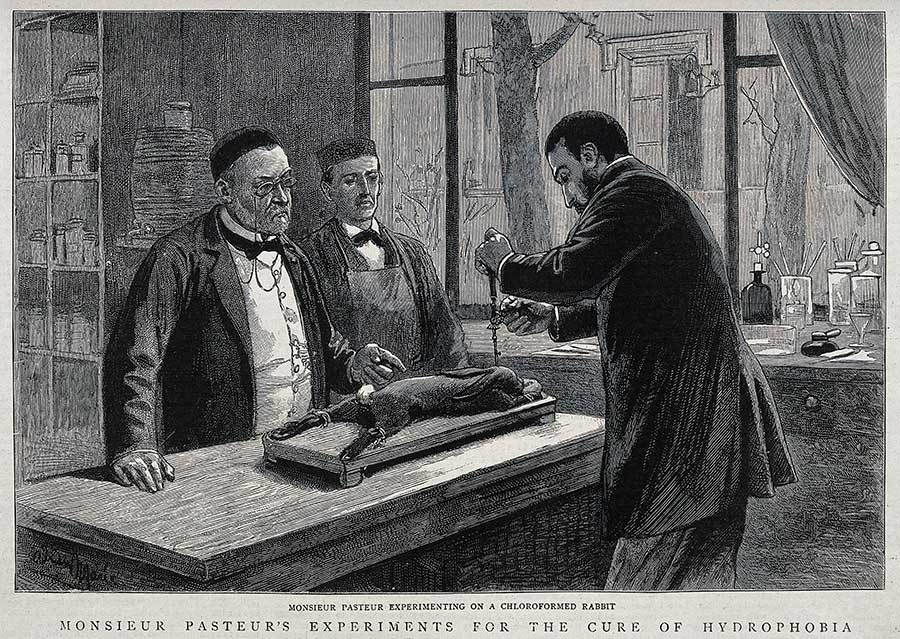

At a lab bench, Pasteur and his assistants hover over the quivering form of a tethered subject. The dog’s thick ropes of drool, Pasteur believes, are loaded with a distinct, disease-causing something. He calls it a “virus,” a still vaguely-defined word he uses to mean an organism that acts like a bacterium, though it eludes observation under the microscope.

Invisible and resistant to in vitro isolation, this presumptive micro-organism can only be studied in the bodies of living creatures, making it a more obscure subject than anthrax, against which Pasteur’s team is now promoting their pioneering vaccine.

Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

Pasteur is not the only scientist probing at rabies, that most arcane of maladies, with the intellectual tools that are on the cusp of refashioning medicine in the image of germ theory. Two years earlier, a young veterinary researcher called Pierre-Victor Galtier reported his experimental inoculation of infected saliva into rabbits, which he described as “the animals of choice for developing the rabies of suspect dogs”. It’s in Galtier’s footsteps that Pasteur begins to follow, though soon he’ll be bushwhacking his way onto new empirical terrain, towards new instrumental discoveries.

For now, to infect his rabbits, he needs a spit sample. He bends towards the dog’s head holding a precise glass instrument, an eye-dropper or a syringe. He draws up into it a measure of the contagious slaver. “It was… at the sight of this awesome tête-a-tête that I saw M. Pasteur at his greatest,” his son-in-law and hagiographer René Vallery-Radot will later recall1.

Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

*

Strange, maybe, to fix upon an instance of physical courage as the exemplar of the scientist’s greatness. By now, Pasteur has built a scientific legacy which includes such hits as pasteurization, a contribution which will mean a whole lot more than safe milk, and the creation of several path-breaking vaccines, which in themselves constitute a transformative recasting of the proposition of a “vaccine” – still named for the cow (vacca) in cowpox, the naturally-occurring, mild and yet handily immunogenic cousin of smallpox – as something that can be engineered from a pathogen, rather than stumbled upon.

He is, in other words, a person of such rare intellectual inventiveness that his career will help condense into one scientific lifetime what might otherwise have been diluted across generations. Against these achievements, risking infection in pursuit of a goal seems an almost banal brand of heroism.

Then again, rabies is not just any infection. To begin with, it’s almost perfectly2 fatal. The appearance of the first rabies symptoms (it starts vaguely: fever, malaise, anxiety; often a tingling at the wound-site) is as good as a death sentence. Neurological signs follow in a matter of days. Within two weeks, the patient slips into a coma, and then into cardio-respiratory failure.

The interval between onset and death is not only a torment for the sufferer, but a spectacle, a grotesque metamorphosis – a change so terrible that it has seemed, at moments in rabies’ long history, to puncture the ontological boundary of humanity. The Suśruta samhita, a Sanskrit medical text dating from (perhaps) the first century, records: “a person bitten by a rabid animal barks and howls like the animal by which he is bitten”, at which point he loses “the functions and faculties of a human subject”. A Babylonian source describes rabies in terms that hint differently at hybridisation: the rabid dog’s “semen is carried in its mouth”, and “where it has bitten, it has left its child”.3

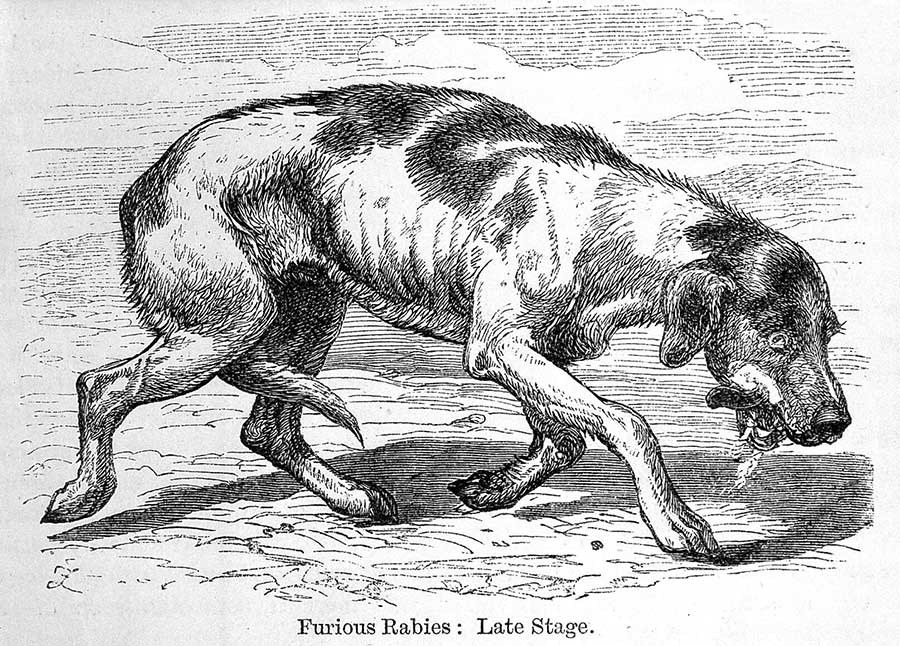

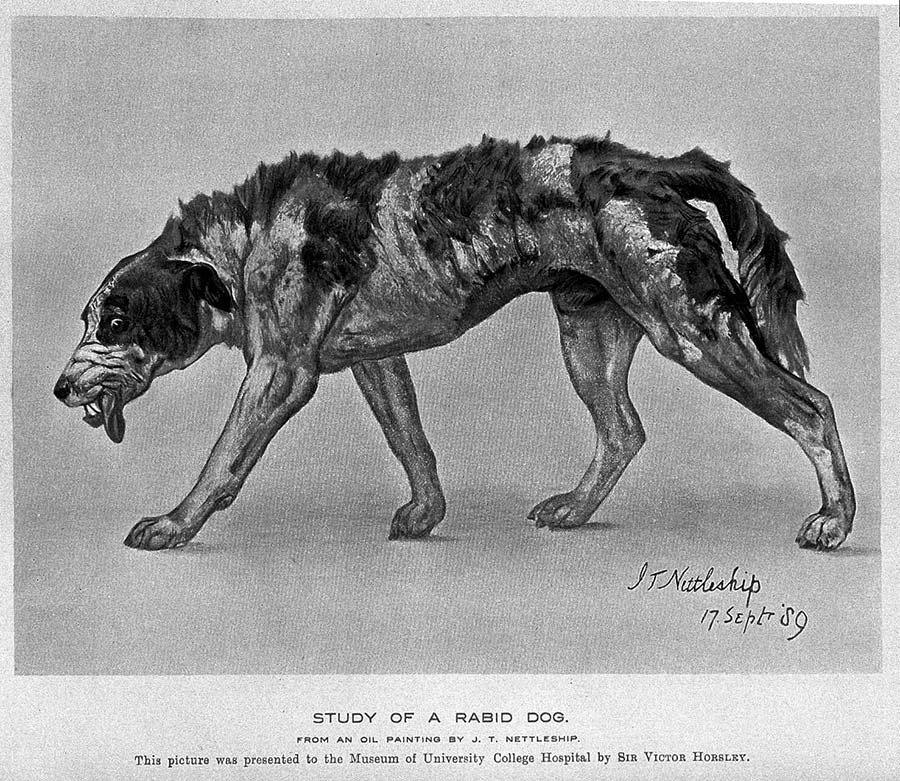

Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

The risk has never been epidemic: rabies has never wiped out a generation or destabilised an economy. Humans could, but don’t, infect other humans. We make a bad vector for a saliva-borne virus; it likes a host with sharper teeth. But rabies is an intimate horror – it comes most often from our suddenly treacherous animal familiars, and appears to warp its victim’s personhood as it kills.

The landmark symptom is hydrophobia: a terror of water, unquenchable thirst. Confusion, hypersalivation, uncontrolled aggression – source of the term “furious rabies” – often follow, accompanied, especially in men, by hypersexual activity. It appears that our carefully subjugated appetites turn feral; something animal, but still as native as a feeling, overwhelms our higher faculties.

Rabbia in Italian means rabies and anger; rage in French and lyssa in Greek straddle the same semantic line. Rabies wrote the script for familiar monsters, like vampires and werewolves, who prowl the shadow spaces of acceptable society and transmit their iniquities by bite.

Have you read?

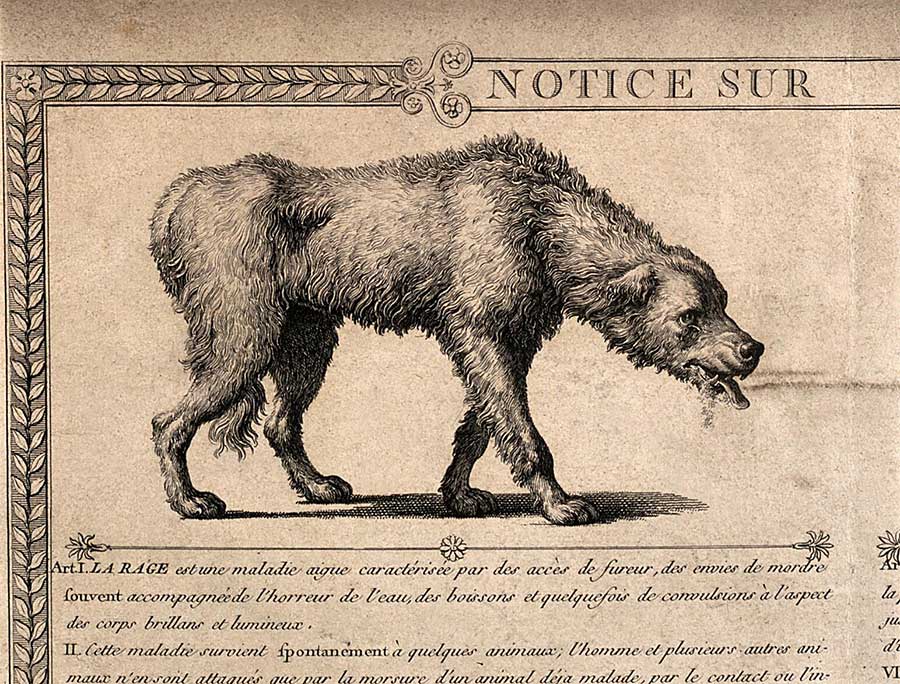

Even thousands of years after Suśruta, many doctors offered little more by way of explanation for the disease than a superstitious shudder. In 1800, Philadelphia’s leading physician Dr Benjamin Rush claimed rabies could generate spontaneously in the human body: an emergence, not an invasion. Half a century later, that etiologic theory looked outdated – but many doctors and veterinarians surveyed in Paris in 18744 still imagine that rabies germinates autonomously in dogs.

Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

*

Pasteur, of course, does not. Though he fails to culture a rabies pathogen from either the saliva he collects, or from the central nervous system, he remains resolute that a specific micro-organism produces the sickness. If he is right and that pathogen exists, he thinks, he can attenuate it and make it yield a vaccine.

Successful immunisation will, in turn, prove that germ theory holds – even in the absence of an isolated pathogen. His close collaborator Emile Roux will later write that Pasteur selected rabies as his object of study because “the rabies virus has always been regarded as the most subtle and the most mysterious of all… he thought that to solve the problem of rabies would be a blessing for humanity and a brilliant triumph for his doctrines.”5 Maybe what Vallery-Radot identifies as “greatness” when he watches Pasteur bend over the mad dog with his glass dropper is about more than physical risk. Maybe it’s about a borderline reckless intellectual self-confidence, a bold scientific wager: high stakes, high reward.

For the wager to pay off, Pasteur needs a more tractable version of the virus. Even introduced via controlled inoculation rather than dog bite, rabies has a long and variable incubation period that makes it tricky to work with. Building on the finding of a hospital physician called Henri Duboué, who reports the localisation of disease in the cerebral matter, Pasteur’s team decides to infect the brain directly, by drilling a hole in the skulls of recipient dogs and inoculating rabid tissue straight onto the dura mater. The method is successful: symptoms appear faster and more predictably.

Next the Pasteur team pass the canine rabies through a chain of 21 rabbits, a procedure that shortens the incubation period further, indicating increased viral virulence. The virus is now strong enough to weaken: attenuation is achieved by desiccating and ageing the spinal cords of rabbits who have died of it.

Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

With iterative adjustments, the attenuated viral matter begins to function well as a vaccine. In 1884, Pasteur writes of his progress to the Emperor of Brazil, who inquires how close he is to producing a human immunisation: “I take two dogs, cause them both to be bitten by a mad dog; I vaccinate one and leave the other without any treatment: the latter dies and the first remains perfectly well. But even when I shall have multiplied examples of the prophylaxis of rabies in dogs, I think my hand will tremble when I go on to Mankind.”

That happens in July 1885, when Joseph Meister, a nine-year old boy from Alsace, is bitten 14 times by a neighbour’s rabid dog. He is rushed to Paris, to Pasteur’s lab. “Since the death of the child appeared inevitable, I resolved, though not without great anxiety, to try the method which had proved consistently successful on the dogs,” the scientist will later write. Over three weeks, beginning sixty hours after the dog attack, Meister is administered 13 progressively virulent rabbit-spine vaccines. He stays well; he grows up. He is the first of many.

His survival is the beginning of the end of rabies, the monster. Under Pasteur’s cool gaze, the virus takes its place in a growing rank of preventable, controllable infections – they become only microbes, not insidious forces with the power to blunt our humanity. That last part, it turns out, is on us.

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you