A RESEARCH STUDY ON THE IMPACT OF PNEUMOCOCCAL VACCINE IN KENYA SHOWS DATA-MINING ELECTRONIC MEDICAL RECORDS IS VITAL TO TRANSFORMING HEALTH CARE

Early one cloudless morning, Oscar Kai was perched on a Yamaha motorcycle clutching his laptop to his chest as he bumped along a dirt road past groves of coconut palms and fields of corn.

He was on his way to a makeshift clinic deep in the Kenyan countryside that is one of 33 taking part in a unique digital study here mapping the success of a new vaccine to help beat childhood illnesses.

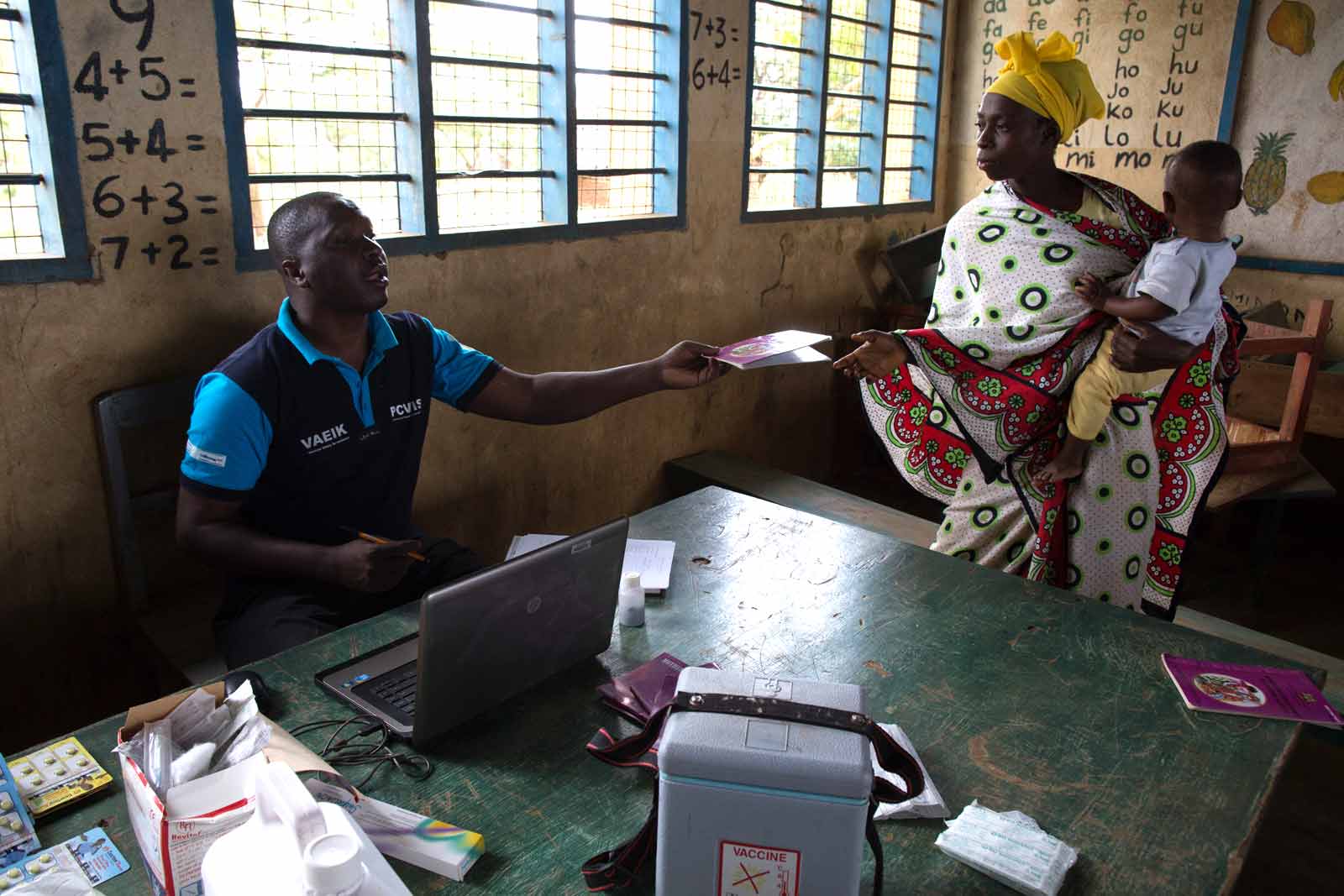

A 20-minute ride later – a distance that would take a woman carrying her baby on foot more than two hours – Mr Kai, 28, set up his laptop on a desk in one of three tin-roofed classrooms at Ngamani Primary School.

Mothers in colourful shawls with babies on their backs began arriving. In their hands, each held a purple A5-sized booklet that, until this new survey, was the main way to document their medical records and those of the children.

Medical digital database

Now that is changing, thanks to Mr Kai and his colleagues on the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine impact study (PCVIS), which is creating a medical digital database of 270,000 people in Kilifi district on Kenya’s Indian Ocean coast.

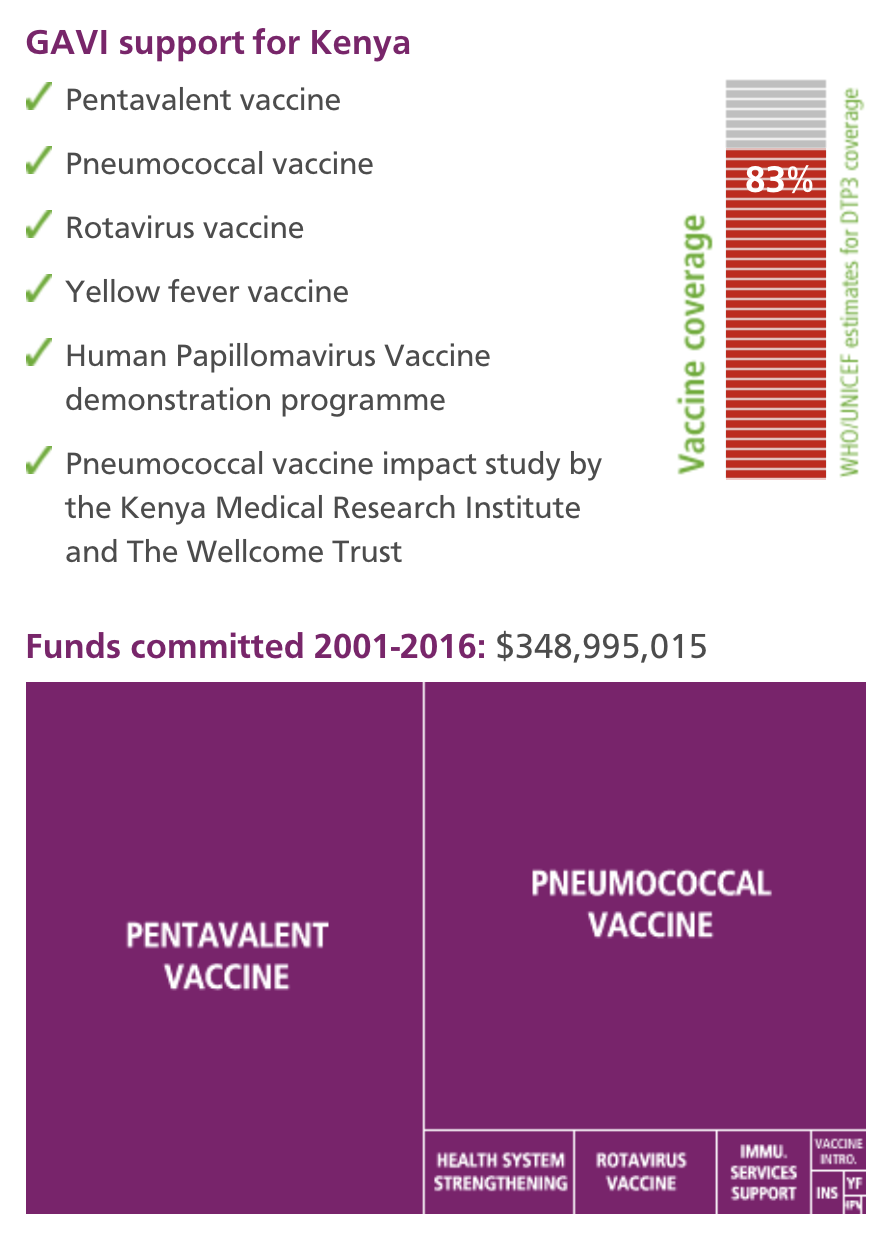

The study, funded by the GAVI Alliance, maps the growing coverage of the new pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV), while concurrently monitoring the ongoing incidence of pneumococcal disease that the vaccine is designed to prevent. Pneumococcal disease, is the leading cause of pneumonia – the world’s number one killer of under fives.

Now seated behind the teacher’s desk at Ngamani, Mr Kai was speaking to Kadzo Chai, 28, whose still-screaming three-month-old daughter Nuru had just been given a second dose of PCV.

Alongside a note of when and where Nuru received that vaccine, her height and weight were updated, and details added of pentavalent, BCG, polio, yellow fever, measles, diphtheria, tetanus and hepatitis B immunisations.

Improve entire health service delivery

Later, these records and those of everyone seen at the clinic that morning will be uploaded to a hard-drive and sent to the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) in Kilifi town which, with The Wellcome Trust, is running the study.

“Because the database is digitised, it means it’s far easier to keep our records fresh, even if children move and access health services in different locations,” says Dr Benjamin Tsofa, the Kenyan health ministry’s chief liaison on the study.

“It is research surveillance, via digitised data capturing, which is embedded in health service delivery structures. An inevitable advantage is that it helps us improve the entire health service delivery."

“It helps us prioritise staff and resource allocation, and track not just PCV but all vaccines and most health interventions for children in our district.”

Monitoring hospital admissions

Separately, the study also tracks pneumococcal disease by monitoring hospital admissions, and it records the prevalence of nasopharyngeal carriage of pneumococcus bacteria with random swab samples of children and adults.

The day after Mr Kai’s outreach clinic, another of his colleagues was also out bumping along dirt tracks on an off-road motorcycle.

Senior field worker Stephen Mangi, 30, was visiting families randomly chosen by the computer for swab tests for the PCVIS’s nasopharyngeal carriage study.

Drop in pneumococcal disease

This is the crucial other side of the impact study: gathering evidence of whether the vaccine is in fact contributing to a drop in pneumococcal disease.

More than 16,000 Kenyans died after pneumococcal infections in 2000, the World Health Organization estimated in 2008; the disease caused 235,000 episodes of pneumonia in the country in the same year.

Later in the afternoon, Mr Mangi returned the samples to the study’s HQ in Kilifi, where Jane Jomo, a lab technologist, transferred them to petri dishes to be incubated overnight to see if bacteria are present.

Across from Miss Jomo’s workbench, another colleague was preparing blood culture samples taken from children admitted to the wards at Kilifi District Hospital.

Incidence of illness

They are testing for streptococcus pneumonia, Haemophilus influenzae type b and staphylococcus aureus, and their results will all be logged in the study database.

"Already, here in Kilifi, the incidence of the illness in children aged five has gone down by approximately two-thirds since the PCV vaccine was introduced in January 2011," says KEMRI’s Anthony Scott.

Doctors and research scientists are however wary of coming to significant conclusions because the study is as yet less than 30 months old.

Give us the evidence

“It is extremely important that we are actually able to measure the impact of the vaccine,” says Dr Juliet Otieno, a paediatric medical officer at Kilifi District Hospital.

“As a clinician, my assumption would be that if we have brought in the vaccine and we see a reduction in cases, then the vaccine is working. But that’s an assumption. The study gives us the evidence.”