How India overcame smallpox

India’s eradication of smallpox with a comprehensive vaccination campaign is the perfect case study for the current COVID-19 vaccine rollout.

- 31 March 2022

- 4 min read

- by Aarushi Verma

When smallpox swamped the world in the 20th Century, it was one of the most lethal illnesses ever known to humanity, killing millions of people before being officially eradicated in 1980.

Smallpox, which is believed to have existed for 3,000 years with a 30% fatality rate, was annihilated through a triumphant vaccination programme. One of the most challenging locations for the global smallpox eradication mission was India. Here smallpox was particularly virulent: the country accounted for 60% of the world’s smallpox cases and it killed one out of every four people who acquired it.

We learn from our past mistakes and the COVID-19 pandemic, which has engulfed the world for the past two years, had essential lessons to learn from the smallpox epidemic. Similar to the smallpox initiative, surveillance, case-finding, screening, contact-tracking, quarantine and communication campaigns to debunk misinformation are central to curbing COVID-19.

The Indian National Smallpox Eradication Programme (NSEP) was founded in 1962 with the goal of vaccinating the whole country within three years. The initiative, however, failed, owing to a lack of coverage and population access. The government changed its policy in 1964, focusing on certain regions of the country where outbreaks were more prevalent, such as Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, and West Bengal.

In 1974, the dark clouds of catastrophe hovered over India, as the country witnessed the worst smallpox epidemic of the century. It was a gruelling task to vaccinate the then-population of 609 million Indians. Smallpox could be contained by mass immunisation campaigns in industrialised countries but these initiatives were less effective in poorer countries with scant health infrastructure. Localised smallpox outbreaks persisted despite extensive immunisation programmes.

The pool of challenges was too colossal for India to swim in – high population density in many areas, great mobility and sporadic huge gatherings, and smaller festivals or fairs provided optimal circumstances for transmission. There were also operational issues in addition to the epidemiological problems. Long after liquid vaccination had been phased out in other nations, India continued to use it.

A deficit of refrigeration facilities hampered the early stages of the programme until freeze-dried vaccines became widely obtainable across the country. Also, the bifurcated needles took a long time to catch on in India. With over 80% of the population residing in remote communities and only having intermittent interaction with health care, the logistical challenges of ensuring adequate vaccination distribution to the periphery compounded the technological issues.

Have you read?

In most nations, vaccinating 80% of the population within five years was thought to be enough to stop smallpox from spreading. The enormous number of births per year in densely populated nations like India, however, rendered this objective impracticable.

While the obstacles standing in the face of a successful vaccination drive against smallpox were many, India vanquished the epidemic. Similar to the containment zone policy the country adopted to tackle COVID-19, a “surveillance-containment“ technique was implemented.

Teams of healthcare personnel would diligently search out any suspected instances of smallpox and the infected persons and their relatives or neighbours would be quarantined and vaccinated right away. Every month, health personnel visited each of the country’s 100 million households.

The majority of the programmes were led by doctors who had great technical qualifications but lacked managerial experience and abilities. Therefore, training the healthcare workers was another paramount necessity. Newly hired employees were given a “Briefing Packet” that included a summary of the smallpox situation in India as well as other field-related material. Posters in native languages were made to urge vaccination uptake, particularly among small children.

The Indian government backed the National Smallpox Eradication Programme. To ensure that all inhabitants had been vaccinated, detailed maps and censuses of homes and residents in the villages within five kilometres of the patient were created and used. It took two years for the country to be proclaimed free of the disease.

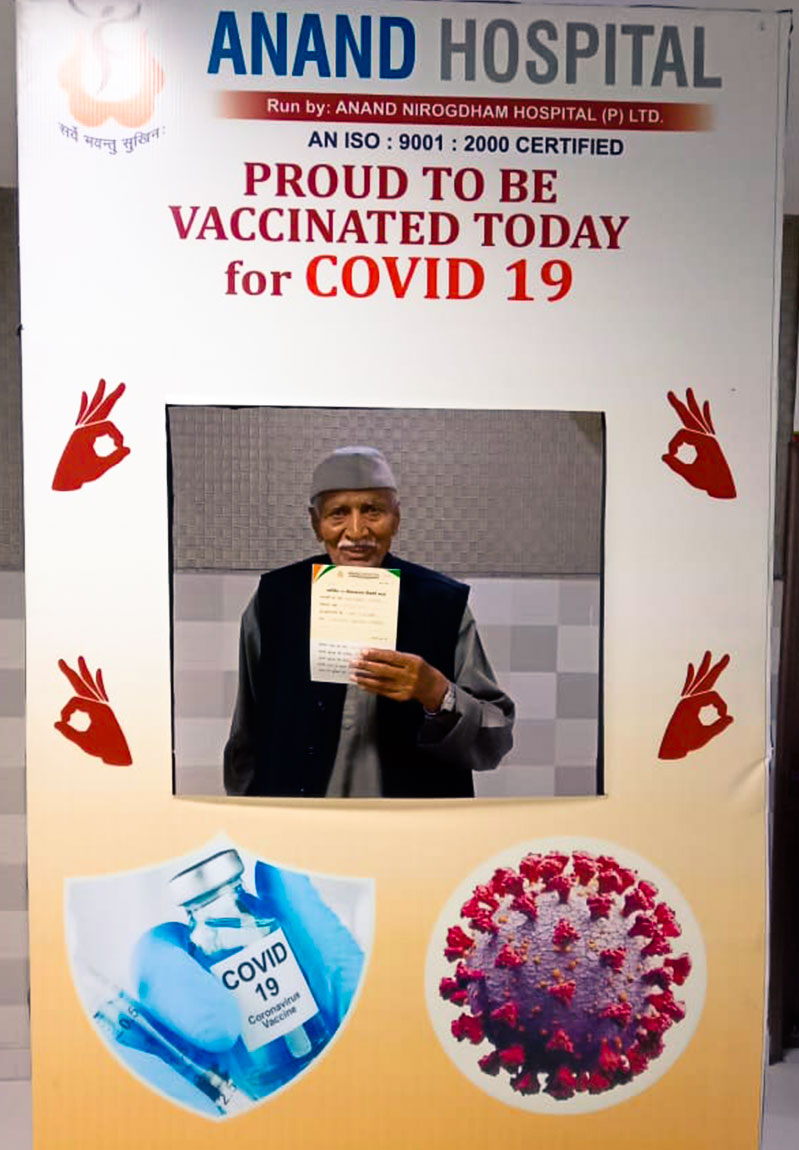

We learn from our past mistakes and the COVID-19 pandemic, which has engulfed the world for the past two years, had essential lessons to learn from the smallpox epidemic. Similar to the smallpox initiative, surveillance, case-finding, screening, contact-tracking, quarantine and communication campaigns to debunk misinformation are central to curbing COVID-19. India held mock vaccination campaigns across the country before the main campaign launch on 16 January 2021, to test the logistics of administering doses and the technology used to manage and monitor vaccine appointments.

Past vaccination triumphs serve as a reminder that immunisation works. Vaccination prevented smallpox infection in 95% of individuals who have received it. Furthermore, the vaccination thwarted or significantly abated the illness when administered within a few days of being exposed to the variola virus. Eventually, India declared itself free of smallpox in 1979.

More from Aarushi Verma

Recommended for you