How to gauge a plague: new analysis sheds light on the meaning of a 6th century pandemic

Disease outbreaks have shaped the world. But how much? New thinking on an early medieval pandemic takes on “plague sceptics” to show that we likely underestimated the impact of the first cross-continental assault of bubonic plague.

- 26 November 2021

- 4 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

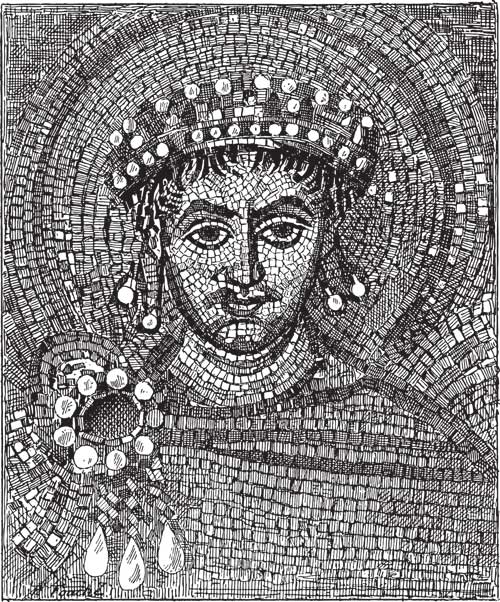

If you’re tracing it through the surviving textual record, the Plague of Justinian – long supposed to be the earliest known pandemic of bubonic plague – first surfaces at Pelusium, an Egyptian port, in the summer of 541 CE. It spreads quickly to Gaza and Alexandria. By the spring of 542, it has reached Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman Empire and a city of maybe half a million people, where some eyewitness chroniclers record death tolls as high as 10,000 a day. By 543 it’s in Gaul; by 544 it’s reported in Ireland. It surges and recurs and blooms across the world map well into the eighth century.

Far from being “inconsequential”, the arrival of plague likely tipped Justinian’s Eastern Roman Empire into crisis.

Read modern genetic research alongside that fragmentary written record, a new study suggests, and the evidence that the disease left a profound and far-reaching imprint on the early medieval world grows only more distinct.

In 2018, for instance, a genetic investigation of human skeletal remains at a 6th century Anglo Saxon burial site at Edix Hill in Cambridgeshire, England, revealed that several of the people buried there died with bubonic plague. According to Cambridge historian Peter Sarris, this discovery offers important new insights. For one, both Edix Hill and previously DNA-tested sites in Bavaria showed that the bubonic plague had penetrated remote, rural areas: “These were areas one might have imagined the plague to have spared.”

Further, the strain of Yersinia pestis, the causative bacterium of bubonic plague, found at Edix Hill turns out to be the oldest lineage yet identified, emerging before examples of Y. pestis recovered in Europe. The plague may have been spreading in England as much as a century before any written source recorded its progress. “In other words,” Sarris writes, “it appeared to be a phenomenon of potentially greater significance than even the literary sources suggested.”

Have you read?

That’s particularly resonant because, in recent years, a “self-consciously revisionist” (Sarris’s words) literature has emerged, making the case that the scale and meaning of the Plague of Justinian has been overblown.

“Some historians remain deeply hostile to regarding external factors such as disease as having a major impact on the development of human society, and ‘plague scepticism’ has had a lot of attention in recent years,” Sarris says. His new paper not only takes issue with the idea of a “maximalist consensus” (there never has been one), it also argues that the effort to construct the Justinianic Plague as an “inconsequential” epidemic relies on a deeply problematic analytical methodology and a certain stubborn blindness to new scientific evidence. Sarris is sharp (the revisionists’ understanding of the scholarship is “facile”; some of their arguments rely on “pure fantasy”) and convincing.

Far from being “inconsequential”, the arrival of plague likely tipped Justinian’s Eastern Roman Empire into crisis. A reduced currency – a series of lightweight coins issued around the time that banking laws began to explicitly reference the disease – points to financial instability. Laws passed to limit the ability of Church tenants to negotiate better may indicate the kinds of shaken-up social dynamics observed during the later Black Death, when survivors of a thinned labouring class found themselves able to leverage new demands. In the legal, literary and numismatic records alone, Sarris finds a “concerted effort” to shore up the institutions of the East Roman state in the face of plague-induced depopulation – to protect landowning institutions, the propertied classes, and state finances from the second-round shocks of so much death.

The Edix Hill DNA suggest widened scope for study, including the possibility of previously unmapped routes of travel for the 6th century plague: to the Mediterranean via the Red Sea, into England perhaps via the Baltic and Scandinavia. What impacts might the pandemic have had where no written records have yet been found that describe it? “The evidence … requires an imaginative and truly interdisciplinary response.” Even just one plague-infected body in eastern England is proof of an entire ecology – fleas, rats, and the forces that allow them to travel. On Twitter, Sarris adds that avenues of inquiry should extend into climate science, archaeology, and paleo-botany.

“Perhaps most excitingly, the genetic evidence will ... lead in directions we can scarcely yet anticipate,” Sarris promises. Meanwhile, there are dots to connect. Lowland Britain went through well-known social, political and economic disruptions in the 5th and early 6th centuries. “Now that we know that bubonic plague was present in sixth-century England, it would be counter-intuitive to deny that plague is likely to have played a part in that process,” Sarris argues.

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you