Groundhog Day on the high seas: A fable of science communication

- 9 February 2022

- 6 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

In September 1740, a well-armed squadron of six British ships set sail for the Pacific under the command of George Anson, a navy captain with a steady, but unremarkable career behind him. His mission: bother the Spanish; nip at their fleet’s heels in the colonies, provoke rebellion in Peru, raid transport galleons for treasure.

J. Mason - Bibliothèque nationale de France

By March of the following year, the squadron was rounding Cape Horn and beginning to fracture. Two ships soon faltered in bad storms and turned back, and scurvy set in among the sailors. “At the latter end of April, there were but a few on board who were not in some degree afflicted with it,” wrote Richard Walter, Anson’s chaplain. That month alone, the flagship Centurion lost 43 crew members to the disease.

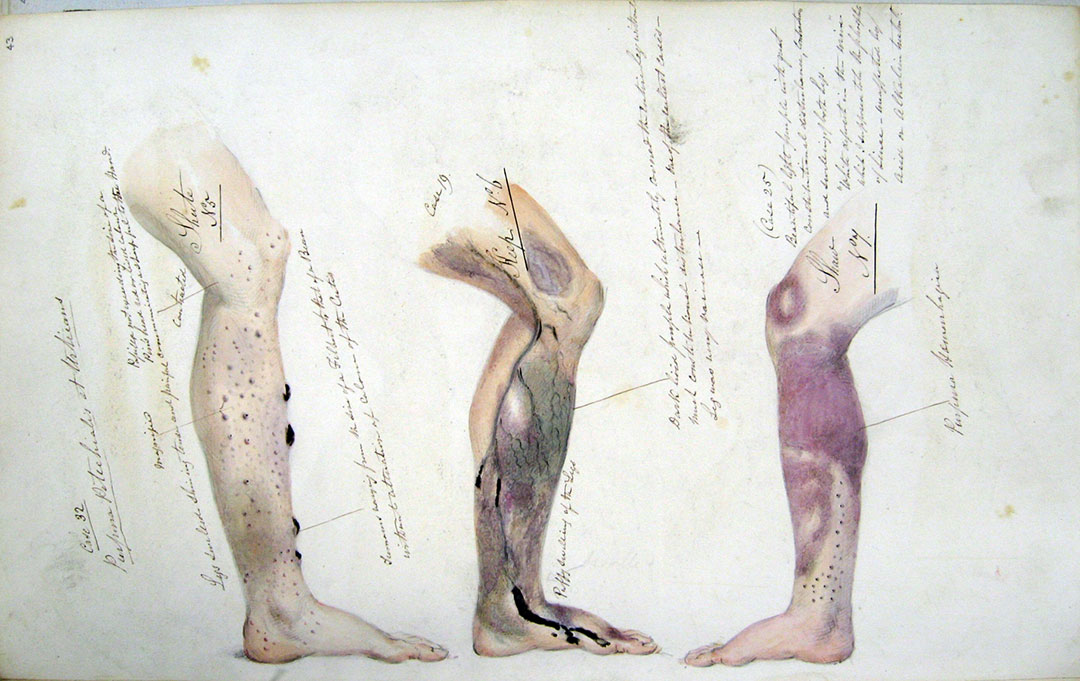

Scurvy was a horrible way to go. Sick sailors’ gums putrefied and turned black, swelling into a pulpy mass studded with wobbling teeth. In time, the teeth fell out. Patient’s legs prickled with blood blisters that grew into stinking, painful ulcers. Fresh wounds refused to scab over; old wounds reopened. Bones that had once been broken re-broke along the scarred seam. Sailors babbled of the foods their bodies craved, hallucinated, sobbed with deep emotion, seemed to change in the essentials of their personalities – observers recorded signs of ‘lunacy’ and ‘idiotism’. Later, nearing death, they grew quiet, drained of energy. Cartilage vanished from the disintegrating bodies, and the ribs of the dying rattled and creaked against their sternums.

From the collections of The National Archives (United Kingdom)

In June, the squadron’s three remaining warships, the Centurion, the Gloucester and the Tryal, limped to anchor at Juan Fernández Island, a pirate hideout off the coast of Chile. “We were by this time reduced to so helpless a condition that out of two hundred and odd men which remained alive, we could not, taking all our watches together, muster hands enough to work the ship in an emergency,” wrote Walter.

The island was the remedy the ailing crew needed: it was lush and beautiful, full of good fresh food to eat. Months passed, the survivors regained their health, regrouped, and got back to the business of harassing Spanish boats and coastal settlements. But eventually, another big ocean crossing had to be attempted, and out there on the endless Pacific, scurvy would again catch up with Anson’s men.

Today, we know that scurvy is what happens to a human body too long deprived of dietary vitamin C, also called ascorbic acid. In a healthy adult, three months without fresh food is enough time for ascorbic acid levels to dip to the point that production of collagen, the body’s glue, is impeded. The same deficiency can impact the synthesis of some of the brain’s chemical messengers, including dopamine and serotonin, which likely explains many of the behavioural and psychiatric symptoms observed in the scurvy-afflicted.

But in Anson’s time, the disease was at once familiar and mysterious – maddeningly predictable, but poorly understood. “Scurvy was an inevitable accompaniment of long periods at sea,” writes Jonathan Lamb in Scurvy: The Disease of Discovery. “Although it was capricious with regard to the speed of its onset and the signs of its presence, no one could avoid it who lived for more than three months on preserved food.” But that observation offered no security in an era of sailing ships, in which commerce and war-making necessitated months-long voyages across the deeps. Between the 15th and 18th centuries, an estimated two million sailors died of it.

Thirteen hundred of Anson’s men numbered among them. The Centurion docked in England in summer 1744, vindicated, in naval terms, after taking a Spanish galleon carrying silver and other treasures in Philippine waters. But it was the only ship of the six to return, and of the almost 2,000 seamen who had sailed with Anson, fewer than 150 had made it safely home.

From the "National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London" – Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-SA-3.0 license

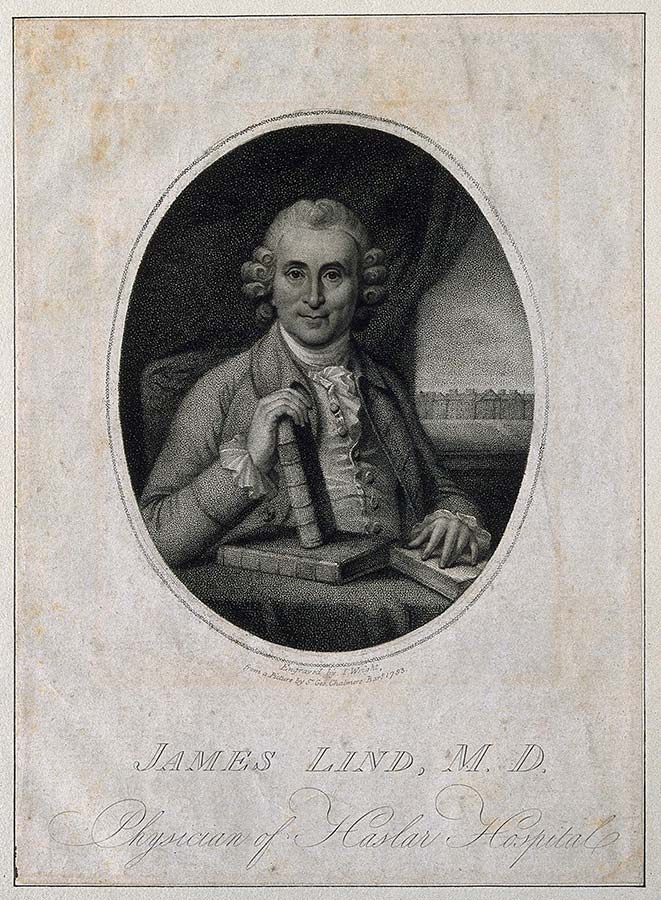

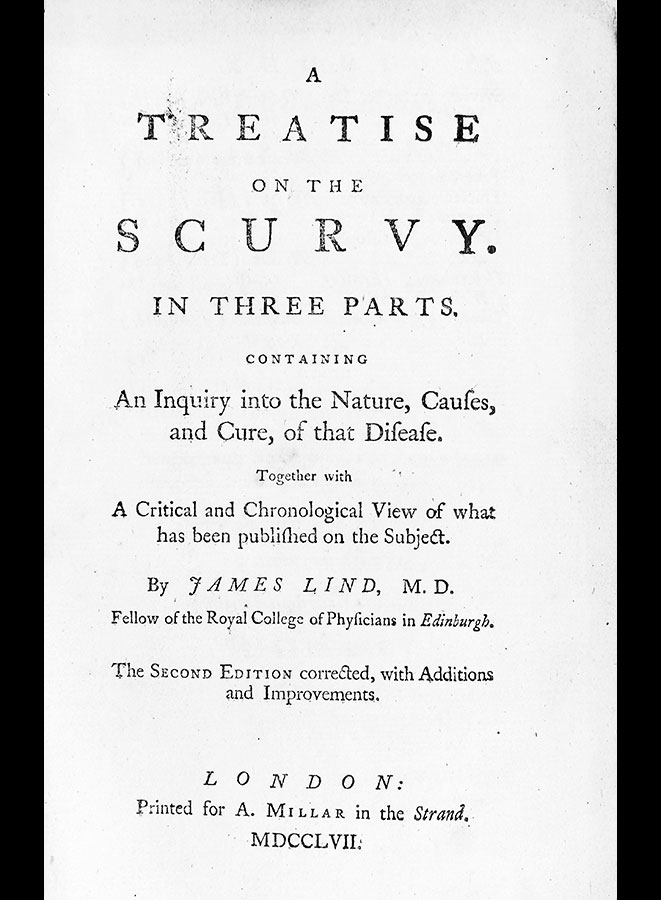

Just three years later, aboard the HMS Salisbury, the Scottish naval surgeon James Lind conducted an experiment that showed that two oranges and a lemon a day could cure scurvy. The trial was simple: 12 scurvy-sick men were split into pairs and assigned a candidate remedy: cider, “elixir of vitriol”, sea-water, a paste of garlic and other ingredients, vinegar, or the citrus fruits. By week’s end, the two lucky men who’d been given oranges and lemons were well enough to nurse the others. When Lind published his findings in 1754, he dedicated his treatise to George Anson.

|

|

It's tempting, at this point, to let the story fall into a familiar shape: the dip of regret for the lives lost just before the cure was found; the redemptive swell at the thought of the countless lives saved. But the discovery of a good therapy, whether by the invention of a bold new technology or the observation of a quite natural effect, is not guaranteed to be a point of inflection in the graph of an illness. Medicine only works when it’s put to use.

Though Lind’s trial lent empirical weight to the scurvy cure, he was far from the first person to propose it. In 1734, a physician from Leiden called Johann Bachstrom had urged the use of fresh fruit and vegetables as a cure, and also concluded that their absence from the diet was the disease’s cause – a connection Lind failed to make. In 1639, John Woodall, author of the Surgeon’s Mate identified fresh fruit and vegetables as key to scurvy’s prevention and cure. In modern-day Canada in 1535, Jacques Cartier’s crew were saved by Native people who knew how to brew a vitamin-C rich spruce beer. “Discoveries of cures for scurvy were simply being lost or discredited and then made again,” writes Lamb.

That amnesiac cycle didn’t end with Lind, who made the crucial error of undervaluing his own discovery and burying the lede. His treatise allotted a skimpy four pages to the HMS Salisbury experiment, spending 450 pages exploring other treatments, including fresh air and exercise. To confuse matters more, Captain Cook, Lind’s contemporary and a louder figure on the naval scene, touted sauerkraut and malt as remedies. Other physicians recommended “earth-bathing”, which was as it sounds: messy and pointless.

It wasn’t until 1795 that the British Admiralty mandated rations of lime juice for sailors (who would become known as “limeys”). Still then the stubborn question wasn’t settled. Leading germ theorists of the late nineteenth century were convinced that scurvy came from eating tainted food. In fact, writes Lamb, “[scurvy’s] cure at sea was a matter of dispute right up until the discovery of vitamin C” by Albert Szent-Györgyi the 1930s. With that discovery came – at last – a comprehensive, compelling “why”.

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you