Question: What is Gavi doing to help contain the Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)?

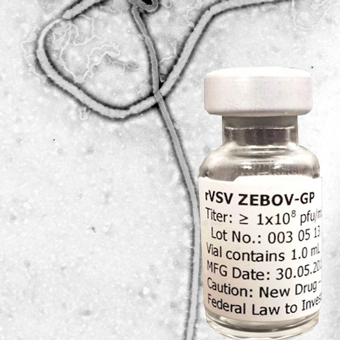

Seth Berkley: Gavi is providing US$ 1 million in operational costs to fund ring vaccination in affected areas of north-west DRC. Thousands of investigational doses of the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine are arriving in the country to help contain the outbreak.

Gavi was instrumental in making these investigational doses available. While the vaccine goes through the licensing process, a 2016 agreement between Gavi and Merck, the developer of rVSV-ZEBOV, ensures that 300,000 investigational doses of the vaccine are available in case of an outbreak. It is these doses that will be used in the DRC.

Q: What will the US$1 million pay for?

SB: This will be used to fund the operational costs for the campaign. This includes funding for the cold chain equipment needed to store the vaccines at extremely low temperatures, the deployment of health workers, transport, critical supplies and other incidental costs of the campaign.

Getting these vaccines to the people who need it will be an enormous logistical challenge. They will need to be transported to one of the most remote parts of the DRC, where there are next to no paved roads, electricity or telecommunications, at a temperature of minus 60 to minus 80 degrees Centigrade.

The vaccines will be kept at this temperature until reaching Mbandaka and Bikoro, when they will be unfrozen prior to vaccination. The doses remain effective for two weeks at temperatures of plus 2 to plus 8 degrees. On top of this, due to the fact that the vaccine is not yet licensed the campaign will be carried out under clinical protocol, which requires Good Clinical Practice (GCP) trained medical staff and informed consent.

Q: What does ring vaccination mean?

rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine. Credit: BlitzKrieg1982

SB: Ring vaccination, as opposed to mass immunisation, controls an outbreak by vaccinating and monitoring anyone who is likely to be infected by an individual who contracts Ebola.

In DRC, this means that contacts of any infected individual, contacts of contacts, healthcare workers and frontline workers at risk will receive the vaccine. This method, the same used to eradicate smallpox, forms a buffer of immune individuals to prevent the spread of the disease.

Q: Is Gavi funding the vaccine?

SB: No, all vaccines are being taken from the emergency stockpile of 300,000 investigational doses made available by Gavi through the 2016 agreement between Gavi and Merck, but are not funded by Gavi. They are being provided by Merck for compassionate use.

Q: What was the agreement between Gavi and Merck?

SB: The Advance Purchase Commitment, announced in January 2016, is the first agreement of its kind. It was designed to incentivise the rapid development of the vaccine as well as guaranteeing investigational doses are available while licensure is being pursued.

Gavi committed US$5 million to buy doses of a fully licensed vaccine as and when it becomes available. Merck agreed to ensure that 300,000 investigational doses of the vaccine is available in case of an outbreak.

Q: Are there risks with carrying out a campaign with an unlicensed vaccine?

SB: Clinical trials have shown the vaccine to be safe and highly effective. The DRC ring vaccination campaign will be taken under clinical protocol – similar to a clinical trial - which requires GCP (Good Clinical Practice) trained medical staff and informed consent.

Q: Why was the vaccine not used during last year’s Ebola outbreak in the DRC?

SB: Preparations were made to deploy the vaccine during the 2017 outbreak, however by the time the national regulatory authorities had given the necessary approvals the outbreak had been contained.

Q: Is the Merck rVSV-ZEBOV Ebola vaccine effective?

Although scientists had researched Ebola vaccines for decades, the lack of a commercial market meant there was no vaccine available to prevent the devastating consequences of West Africa’s outbreak from 2013-2015. Learn how Gavi’s public partnership model has played a critical role in accelerating the development of the vaccine that is being deployed against DRC’s 2018 outbreak.

Read the full story on Got vaccines? Got life!

SB: In December 2016, WHO published the results from the Guinea ring vaccination trial, showing that the world’s first Ebola vaccine provides substantial protection. Among the thousands of people who consented to be vaccinated, no cases of Ebola virus disease occurred 10 or more days after vaccination. The estimated vaccine effectiveness was 100% with a 95% Confidence Interval between 79.3 and 100%.

In other words, the estimated vaccine effectiveness was 100% and we are 95% confident that the actual effectiveness is between 79.3 % and 100%. Additional statistical analyses were made, which all confirmed that the vaccine offered substantial protection against Ebola virus disease.

The team conducting and analysing the results included well-known leading experts in the field. The trial results were analysed in collaboration with experts from the University of Florida, the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the University of Bern, and the National Institute of Public Health of Norway.

Q: What happened during the outbreak in West Africa 2013-2016?

SB: The outbreak in West Africa that began in 2014 was the largest to date – there were more cases and more deaths than all previous outbreaks combined. The outbreak began in Guinea in 2013 and later spread to Sierra Leone and Liberia. Lack of capacity in Guinea led to the outbreak being initially misdiagnosed as cholera and then as Lassa fever, slowing the response.

Unlike previous Ebola outbreaks, which were largely confined to remote rural areas, cities in all three countries became the epicentres of the 2014-2016 outbreak. By March 2016, when the Director-General of the WHO declared the end of the outbreak as a ‘public health emergency of international concern,’ there had been over 28600 cases and over 11300 deaths.

Damaged public health infrastructures, high population mobility, and traditional funeral and burial practices involving direct contact with the body all contributed to the scale of the outbreak.