6 historic experiments that helped pave the way for modern clinical research

The story of the clinical trial is longer and weirder than you might think.

- 16 February 2022

- 7 min read

- by Maya Prabhu

But does it work? It’s a question physicians and healers have tried to answer convincingly since well before the scientific method was an established concept. Today, we have elaborate codes of practice to ensure that multiphase clinical trials produce robust, meaningful, replicable results. That hasn’t always been true – what qualified as proof was often little more than embedded superstition – but glimmers of ‘modern’ approaches to clinical evidence-gathering show up even in the furthest reaches of the historical record.

1. A different kind of Biblical trial (Babylon, c. 6th century BCE)

The first documented clinical experiment is probably also history’s most-heavily circulated. The Old Testament has the details: having conquered Judah, Babylon’s King Nebuchadnezzar brought several young noblemen, including Daniel of lion’s den fame, back from Jerusalem to live at his court in genteel captivity. There, as part of a programme of training, they were expected to eat the meat and wine the King served his courtiers. But Daniel was unwilling to “defile himself” with a diet that violated his customs.

He proposed a study: “Test [us] for ten days; let us be given vegetables to eat and water to drink. Then let our appearance and [that] of the youths who eat the king’s rich food be observed.” Ten days in, Daniel and his friends “appeared fairer and fatter in flesh” than the youths who ate the king’s heavy fare. Faced with this evidence, the King yielded and allowed them to maintain their traditional diet.

Credit: Wellcome Collection. Public Domain Mark

“Here we have all the elements of the so-called ‘modern’ clinical trial,” writes Allan Gaw in Trial By Fire: Lessons from the History of Clinical Trials. An experiment is designed to test a hypothesis – that what we eat and drink affects our appearance. Observations are made, conclusions are drawn: “Finally, and I would argue, most importantly, the findings are published.”

2. Ginseng vs. nothing (China, 11th century CE)

Long before the use of control groups – which might today include patients who are not treated at all, or patients who receive a placebo, or patients who receive a standard treatment rather than an experimental one – became standard practice in medical trials, scientific minds spotted the value in staging a comparison between an intervention and its absence.

The Ben Cao Tu Jing (Atlas of Materia Medica), a Chinese pharmacopoeia first published in 1061, includes a description of such a set-up. “It was said that in order to evaluate the effect of genuine Shangdang ginseng, two persons were asked to run together,” records the text. “One was given the ginseng while the other ran without. After running for approximately three to five li [equivalent to 1500-2500m], the one without the ginseng developed severe shortness of breath, while the one who took the ginseng breathed evenly and smoothly.”

Have you read?

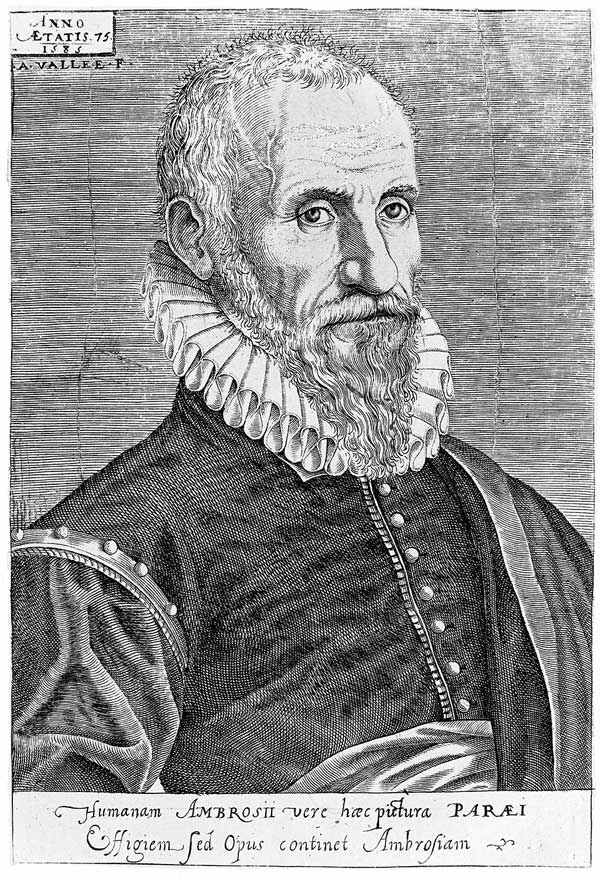

3. An accidental battlefield laboratory (France, 1537)

In 1537, France was at war with the Holy Roman Emperor and a young French surgeon called Ambroise Paré was on the Piedmont front. So many soldiers were injured that the boiling oil conventionally used to cauterise unclean battle wounds was running short. Paré was forced to improvise: “At length my oil lacked and I was constrained to apply in its place a digestive made of yolks of eggs, oil of roses and turpentine,” he recorded.

Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

An anxious night passed as Paré dreaded the consequences of his unplanned experiment. “[I feared] that by lack of cauterization I would find the wounded upon which I had not used the said oil dead from the poison.” But in the morning, he found the inverse result: the soldiers he had treated with his invented medicine were in less pain, their wounds less swollen and inflamed than the wounds of their traditionally-treated counterparts.

He hadn’t contrived the experiment deliberately in response to a hypothesis, but that didn’t stop him from drawing an important conclusion: “I determined never again to burn thus so cruelly the poor wounded by arquebuses.” Some call Paré’s accidental process the first clinical trial of a novel therapy.

4. Oranges and lemons and a whole bunch of controlled variables (Aboard the HMS Salisbury, 1747)

The HMS Salisbury had been at sea for some eight weeks when scurvy hit its crew. James Lind, the ship’s surgeon, set out to test a theory that the sickness could be cured with acids. He chose 12 patients, split them into pairs, and assigned each pair a different therapy: cider, “elixir of vitriol”, vinegar, sea-water, garlic and barley paste, or oranges and lemons.

Crucially, he was careful to begin with patients displaying similar clinical pictures: “their cases were as similar as I could have them", he wrote. “They all in general had putrid gums, the spots and lassitude, with weakness of their knees.” He made a careful effort to manage the untested variables: “They lay together in one place, being a proper apartment for the sick in the fore-hold; and had one diet common to all.”

The results were striking. After a week, the patients on the orange-and-lemon cure were well enough to nurse the others. Though Lind’s results failed to have the immediate and life-saving impact that they should have, his experiment is a landmark example of controlled empiricism in medical research.

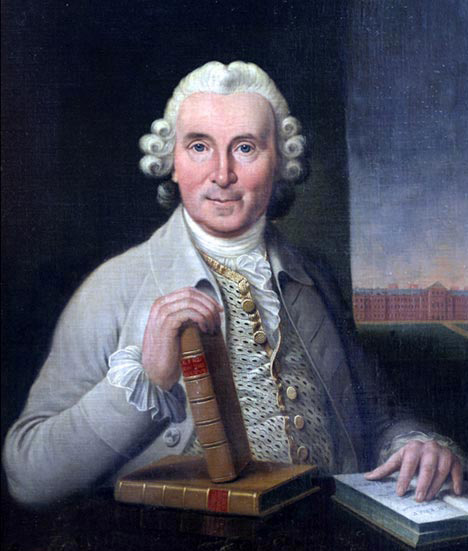

5. Mesmer vs. Ben Franklin: unmasking the placebo effect (France, 1784)

Since the late 1770s, a charismatic German physician called Franz Mesmer had been making waves in Parisian society. His theory: illness was caused by a disruption to our natural electromagnetic force and a cure could be effected by the manipulation of these “magnetic fluxes”. Mesmer’s “animal magnetism” therapy was unfailingly spectacular, the setting far from clinical: alongside magnetic water and iron rods, his interventions featured strange music, low lighting, a sensual healing touch and lilac silk robes. They culminated, frequently, in hysterical crises of release for the patient.

Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

When the King ordered an investigation into Mesmer’s methods, he appointed as his commission’s head the American ambassador to France: the polymathic and by now septuagenarian Benjamin Franklin – a man with a cultivated sense of science and scepticism. Though Mesmer was unwilling to participate personally in in the review, Franklin and his colleagues understood that if they could disprove the existence of his magnetic fluxes, they would have disproved Mesmer’s approach. The experiments they devised stand out as the first example of blinded design in clinical trials.

Subjects were blindfolded and presented, in various ways, with either ‘mesmerised’ – or magnetised – objects or un-altered objects. The results made it clear that “imagination” was capable of producing the same effects as mesmerism. For example, a woman who believed herself to be drinking mesmerised water collapsed in a crisis after four cups, not realising the water was plain – in other words, a placebo. Though “placebo” wouldn’t enter the medical lexicon for another year, Allan Gaw writes, “Franklin and the French Royal Commissioners are credited with being the first to use placebos in a clinical research setting.”

6. The first randomised controlled trial (UK, 1948)

When it came to managing bias in trials, allocation – the divvying up of the different treatments to patients – was a persistent concern. Until the 1940s, studies typically relied on alternate assignments, so that if patient one received, say, a control, patient two would receive the experimental therapy. But if the investigator knew what treatment the last patient was assigned, he or she might consciously or unconsciously influence the next assignment in a way that could finally throw the trial’s validity.

In 1946, a British statistician called Austin Bradford Hill, who was designing a trial of the antibiotic streptomycin for the treatment of TB, took up this problem. His task was to figure out a mechanism for more authentic randomization, one that eliminated the connection between the order in which patients showed up to enrol, and the treatment they received.

This file is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license.

Hill’s system would revolutionise the way clinical trials were done. Each time a patient was enrolled in the trial, a sealed envelope containing a card was opened at the project’s main office. If the card was marked “S”, the patient went into streptomycin treatment. If the card read “C”, the patient received the control treatment. Investigators were blind to the statistical series that produced the cards.

To further protect the experiment from the creep of bias, the TB patients’ X-rays were analysed by experts who were kept into the dark about those patients’ treatment assignments. “Basically, he cracked it, and what we’ve done since is refined what he proposed,” Dr Madhu Davies, co-editor of A Quick Guide to Clinical Trials, told the Canadian Medical Association Journal in 2009.

More from Maya Prabhu

Recommended for you